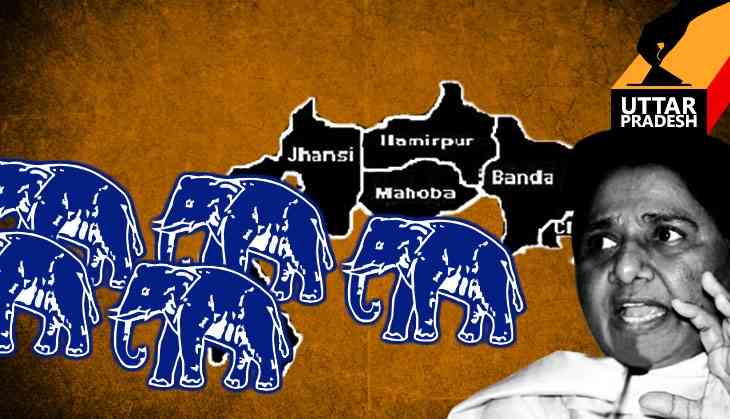

Why drought migration may damage the BSP's prospects in Bundelkhand

In the Harijan quarter of Manpur village in Narayani, Banda, many houses are locked. “Log palayan kar gaye hain (people have migrated),” a villager explains.

In Manpur and other villages across arid Bundelkhand, years of drought and near-famine have forced lakhs of people to migrate in search of work. Indeed, migration is major problem here. Yet, political parties, the villagers complain, haven't taken up the issue head on. “Each time PM goes to a foreign country, we think he has gone to get some foreign companies to set up factories in our area. None has come,” Shaktideen Kharwar, of Damaura village, joked. He is one of nearly 200 people from the village who work in other towns.

Since it's the poorest who form the majority of the migrants – Dalits and Adivasis – it could likely impact the BSP's chances in the election, political analysts and social activists claim. The BSP, like the SP, is facing a crisis since a section of its support base among the Dalits, including the Jatavs who are said to form the backbone of its votebank, voted for Narendra Modi in the 2014 Lok Sabha election.

Also Read: In drought-ravaged Bundelkhand, voters have few demands – water, work

“In our surveys we have found that it is mostly the members of the Dalit community who have migrated, although there are OBCs as well. This will mostly impact the BSP,” says Raja Bhaiya, who runs Vidya Dhan Samiti, an NGO that works with the villagers in Banda.

“The election is just three days away and I am seeing 30-40 per cent of the voters are not in the villages,” Abhimanyu Singh, an activist in Chitrakoot, points out. “Although members of all communities have migrated after seven years of relentless drought and famine, of which 2016 was the worst year, the maximum migration has happened from the Dalit communities. Hence, the BSP will be the most affected.”

Bundelkhand's 19 assembly constituencies will vote on 23 February in the fourth phase. The BSP won seven of these in 2012, cornering around 26.2% of the vote, while the SP won five, the Congress four and the BJP a solitary seat.

“We have eight bighas of land but nothing grows on it. We sowed gram the last season, but did not get anything. Whatever grew was consumed by the cattle left in the fields by other farmers who cannot feed them,” says Shakuntala, who lives in the Harijan quarter. Her husband left for Mathura a couple of weeks ago where he now works as a mason. “There is no work here. How will he feed us,” she says, her two children and old father-in-law, who works as a chowkidar, listening. “Mayawati did a lot of work here, killed criminals,” Mayadeen, the father-in-law, adds. The villagers say the situation got so bad that even hay for cattle was selling at Rs 800 a quintal instead of the usual Rs 200

“Most Harijans have no land. And even if some have got land on lease from the government, nothing grows in this arid place, where monsoon rains only come once in a few years,” says Jagratiya. She is the only one in her family still in the village. “One of my sons and my husband work in Surat and the other son is in Mathura,” she points out. Her friend from the same village, Dudiya, interjects. “Even my son has left the village. He had no work here. He now sells kulfi in Hasanpur for a living.” Hasanpur is a small town near Moradabad in western UP.

Also Read: Demonetisation after drought: Bundelkhand's cup of woes runs over

“Seventy per cent of our community has left for other towns,” says Raju Bansal of Amarpur village in Manikpur. “We are a third class community. Nobody bothers about us,” he adds, referring to his caste, the Balmikis. “We don't have any land so we are not even entitled to the drought relief money that landowners get. Mayawati ne bohot sahara diya tha (Mayawati helped us though).”

Most people who migrate from Bundelkhand work as daily wagers. Many opt for the brick kilns of Haryana, Uttar Pradesh and Punjab, while others choose industrial towns such as Surat, Mumbai and Delhi. Most return home during the harvest season when there is work in the villages.

Brick kilns offer more money than other daily wage jobs. “You get paid 650 rupees for every 1,000 brick you make. So entire families move to the brick kilns for three-four months every year and then come back to the village after earning some money,” explains Pramod Kumar of Bijanagar, a village about 2.5 km from Mahoba. He points to other villagers standing near him, each of whom has a relative away from home. “The city is not very far. Yet there are no jobs. Did you see any factory in this region except for the stone crushers?” he asks.

This season has been bad for brick kilns too, as they started operations late. “Earlier, the contractors would come to the village in October-November and pay money in advance to those interested to work in the kilns. This year, after note bandi, nobody came,” Pramod says, explaining how some villagers have left to find other jobs while the desperate ones have still gone to the kilns.

“Note bandi karke Modiji ne gareebon ki hatya kar di (Modi murdered the poor with demonetisation),” says Shivnarayan Kol of Kekramar village in Manikpur. “It is mostly the Kols who have gone out for work from this village.”

In the neighbouring Morketa, too, Kol families have gone away in search of work.

And most of those who are away for work are not expected to return and vote, the villagers say. “I have come back because I am not well and doctors and hospitals are too expensive in Ghaziabad,” says Kharwar.

“Why will they come just to vote, spending their own money?” asks Pramod.

The situation is different at the time of panchayat elections, when candidates spend money to being the villagers back for polling day. Also, the candidates in local polls have relations with the villagers, giving them reason to come back and vote.

Not for this election. “Nobody has approached my husband to come back to vote,” Shakuntala says.

“We know it is an issue,” says Santu Kumar Ahirwar, a local BSP functionary in Naraini, Banda. “We are trying to ensure that they come back.”

Also Read: BJP's formula to win UP: play communal ball with SP

First published: 22 February 2017, 20:57 IST