50 years of Naxalbari: with Sangh in power, a new political energy needed now

It is now 50 years since Naxalbari, an otherwise obscure area in the Darjeeling district of West Bengal near the India-Nepal border, stormed into India's political vocabulary.

It was a peasant uprising with a difference, which raised the question of changing land relations to the level of a change in the class configuration of state power.

The state did all it could to try and crush the communist-led upsurge right at its inception. Custodial killings, fake encounters, mass extermination of young activists and their family members, third-degree torture, indiscriminate indefinite detention without trial – much that has now become routine in terms of state repression actually originated as the state response to Naxalbari.

Alongside brutal repression, the state also resorted to systematic demonisation of the Naxalbari movement, equating Naxalism with terrorism and dubbing it the biggest internal threat to national security.

Yet, ahead of the 50th anniversary of the Naxalbari uprising, we saw Bharatiya Janata Party president Amit Shah visit Naxalbari with great fanfare, making it the starting point of his Mission Bengal. Intriguingly enough, soon after the first leg of his Bengal visit was over, the couple who had hosted him in Naxalbari left the BJP to migrate to the Trinamool Congress!

The tug-of-war over Naxalbari between the parties ruling at the Centre and in the state makes one thing crystal clear: despite so much repression and demonisation, Naxalbari still remains a potent symbol, even in the calculations of the powers-that-be who have declared Naxalbari dead many times over.

Inspiration for Naxalbari

Let us, however, move beyond symbolism and turn to the historical substance of Naxalbari and its contemporary resonance. Naxalbari was no sudden spontaneous upsurge of the peasantry, like the ones we see in many places in the ongoing resistance of peasants and adivasis against corporate land grab.

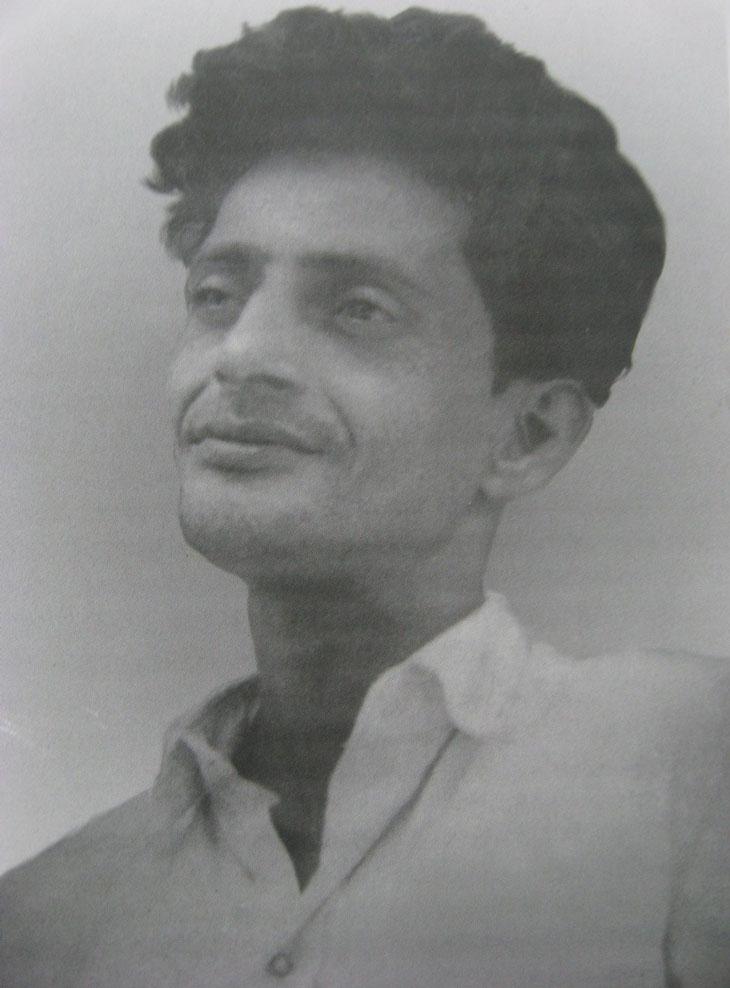

It was rooted in a conscious, organised and sustained communist attempt to resurrect the spirit of Tebhaga and Telangana. Tebhaga was a revolutionary struggle of the peasantry in the undivided Bengal of the 1940s, remarkable for its class unity and militancy in the face of a communally vitiated social environment. Charu Majumdar and many of his fellow architects and organisers of Naxalbari were activists of the Tebhaga agitation, and Naxalbari and the adjoining areas of North Bengal were major centres of that historic peasant upheaval.

Accompanying this conscious endeavour was a sharp ideological struggle within the communist movement. Ever since the Tebhaga-Telangana days, there was a serious view within the communist movement that felt that the peasant question and the potential of an agrarian revolution had been grossly neglected in India.

The debate got sharpened after the communist leadership officially withdrew the Telangana struggle, and effectively subordinated the extra-parliamentary dimension of the movement to a predominantly parliamentary perspective.

The famous 'Eight Documents' of Charu Majumdar give an authentic and insightful account of this ideological-political debate.

Roots of Naxalbari

It is important to emphasise the background and the roots of Naxalbari within the Indian communist movement, for far too often, we find accounts of Naxalbari that treat it as an imitation of the Chinese experience of the Cultural Revolution.

Naxalbari of course drew a lot of inspiration from China, the Communist Party of China termed it the Spring Thunder in India, and Indian communist revolutionaries even went to the extent of calling China's Chairman Mao Zedong their own Chairman.

But to appreciate the essence of Naxalbari, we will have to locate it firmly within the Indian context of the turbulent 1960s – the deepening crisis of the ruling classes and the Indian State, and the deeply felt urge within the communist movement to treat the juncture as a revolutionary opportunity for the Indian people.

Two successive wars had placed a heavy economic burden on the people. The dreams ignited during the freedom movement dissolved into deep mass disillusionment amid massive food shortages, soaring prices, stagnant agriculture and growing unemployment.

Following the demises of Nehru and his successor Lal Bahadur Shastri, the Congress was caught in a clumsy process of leadership transition. The first signs of its electoral decline could be seen with the party losing power in as many as nine states in 1967. In West Bengal too, the Congress got voted out by a coalition government, in which the communists were the biggest component.

It was against this backdrop that Naxalbari happened, and when the state chose to crush the peasant rebellion, communist revolutionaries responded with a call to spread the prairie fire of Naxalbari across the country and turn the 1970s into the decade of liberation for the Indian people.

Within two years of the Naxalbari uprising, the architects of Naxalbari had taken the next step of forming a new Communist Party called the Communist Party of India (Marxist-Leninist). The new party, which evoked tremendous response among revolutionary communist ranks, and spread fast across the length and breadth of India, stood in sharp contrast to its two predecessors, the CPI and the CPI (M).

The CPI had effectively abandoned the great Telangana uprising, but the CPI (ML) was formed with the declared goal of fostering and spreading the fire of Naxalbari. The CPI (M) was formed through a vertical split within the CPI, and the founding members of the CPI (M) were all senior leaders of the undivided CPI. The founding leaders of CPI (ML) were mostly district level leaders of the CPI (M).

Most significantly, given the CPI (ML) understanding of agrarian revolution as the key to the democratisation of the society and the landless poor as the leading force of agrarian change, the new party found a more receptive audience among the oppressed rural poor, mostly Dalits, extreme backward castes and adivasis in social terms.

The deep roots among the oppressed poor has been a great source of the fighting strength and resilience of the CPI (ML) in the face of acute state repression and feudal violence, perpetrated often by state-patronised private armies of landlords. No other party and movement has demonstrated the kind of resilience the CPI (ML) has displayed in the face of such severe repression.

Charu Majumdar's doctrine

Media analysts often tend to identify the CPI (ML), or what is popularly described as Naxalism, with the specific forms of struggle adopted by the CPI (ML) in its initial phase. The CPI (ML) had characterised the situation in the late 1960s as a favourable revolutionary situation, and accordingly, revolution itself became the direct and immediate agenda.

Partial demands, everyday work of mass organisations, and electoral intervention, all took a back seat in that scheme of things, and armed struggle became the central focus.

But if one takes a slightly longer-term view of the emergence and evolution of the CPI (ML), it becomes clear that the CPI (ML) never made a fetish of any particular form of struggle – the efficacy and suitability of specific forms depending on the given situation and objective conditions.

The Eight Documents that laid down the ideological-political foundation of Naxalbari did not rule out any form of struggle. Even while treating armed struggle as the central form of mobilisation and action, Charu Majumdar always warned against the danger of militarism, and insisted on keeping politics in command and unleashing the initiative of the masses.

And in the wake of severe military crackdown and adverse changes in the situation following the consolidation of the Indira Gandhi regime after the 1971 electoral victory and the Bangladesh war, in his last writing, Charu Majumdar stressed the need for a broad anti-autocratic coalition of Left and democratic forces. “The interests of the people are the interests of the Party,” he reminded his comrades.

The revival of the CPI (ML) following the massive setback of the 1970s posed a great challenge to the communist revolutionary camp. As often happens after every setback, some sections virtually began to disown the entire movement, calling the whole thing a big blunder. At the other end of the spectrum were those who continued to hold armed struggle as the exclusive form and arena of struggle, eventually cutting themselves off from the CPI (ML) stream and rechristening their organisation as the CPI (Maoist).

While the Maoists have found some favourable terrain in the forests of central India, the rejuvenated CPI(ML) struck deep roots among the oppressed rural poor in Bihar and Jharkhand, making its presence felt through powerful struggles of the rural poor and assertion of radical students and women. The mass support has also led to a string of electoral victories and sustained political intervention in states like Bihar and Jharkhand.

During the first phase of showdown with the state, there had been little opportunity for the fledgling party to review its experience and draw appropriate lessons. Rectification of old mistakes has opened up new vistas of struggle and assertion of the oppressed and exploited people for the whole gamut of their rights.

The spirit of Naxalbari

As we observe the 50th anniversary of the historic uprising, let us look at the major takeaways from the movement and their contemporary relevance. A few points readily demand our attention.

Naxalbari was a peasant revolt that had the turned the pain and anger of the oppressed landless poor into a powerful resistance. This message of Naxalbari cannot but resonate loud and clear in the face of today's acute agrarian crisis. The pain has taken a heavy toll, hundreds of thousands of debt-stricken crisis-ridden peasants have had to take their own lives, but the flame of resistance burns bright against every instance of forcible land acquisition and agrarian injustice.

Naxalbari was an upsurge of the radical youth, comparable in its intensity, scale and sacrifice with the role of the students in the freedom movement. Urban students, in their thousands, plunging headlong into revolutionary politics, fanning into the countryside to get integrated with the oppressed rural poor, and articulating a new diction of 'people first' patriotism – this spirit of Naxalbari today resonates across university campuses as the twin processes of WTO-dictated commercialisation and Sanghi subversion unleash a veritable war on the student community and turn every university into a battlefield.

At a time when nationalism is being sought to be redefined as unmitigated Hindu majoritarianism, the 'people first' patriotism popularised by Naxalbari provides the most effective bulwark to defend the democratic diversity of multicultural India against the fascist project of homogenisation and regimentation.

Naxalbari energy needed again

With Naxalbari began a new approach to Indian history. Defying the dominant framework of viewing history through the eyes of the rulers, the gaze shifted to the history of the oppressed. The unsung heroes of adivasi rebellions and peasant revolts finally began to make their presence felt on the pages of history, the subaltern school of historiography announced its arrival.

Today, we see a war on history in India from the other end. Ancient history is being replaced by mythology, medieval history is once again being subjected to colonial-communal stereotypes, and modern history has become the object of a 'smash and grab' operation.

From Gandhi and Subhas Bose to Bhagat Singh and Ambedkar, every popular icon of modern history is up for grabs. The saffron rulers are desperate to bridge their 'history deficit'!

Most crucially, Naxalbari was a great moment of radicalisation of the Indian communist movement. It gave rise to a new paradigm of class struggle that is not confined to the economic realm or the parameters of parliamentary politics, but committed to fight out oppression and injustice in every sphere of social existence. Issues of caste and gender, race and nationality, language and culture found their rightful place in this new praxis of class struggle.

Today, the Sangh brigade is in power with its Hindi-Hindu-Hindustan agenda. It is desperate to bulldoze India under the twin wheels of corporate plunder and communal polarisation. In this scenario, the radical energy and resilience of Naxalbari could perhaps never be more needed.

First published: 12 May 2017, 18:04 IST