Turns out, viruses with slower impact tend to alter the human body's response to vaccines and pathogens alike.

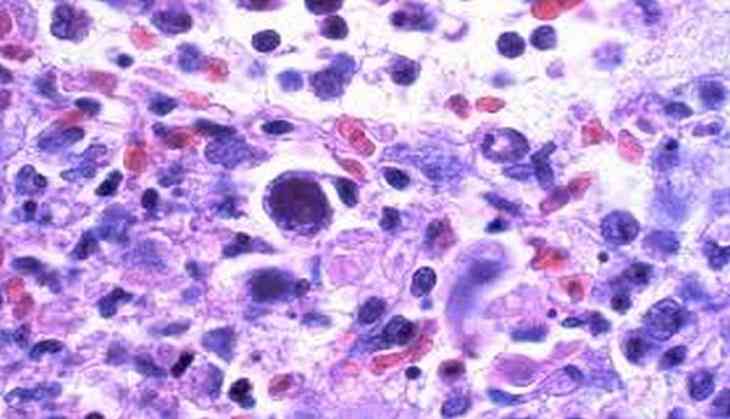

A research conducted at the University of California has shown that low levels of cytomegalovirus (CMV) have a significant impact on microbe and immune cell populations and how the immune system responds to the influenza vaccine.

"Subclinical CMV infection alters the immune system and the gut microbiota in the host and that impacts how we respond to vaccines, environmental stimuli, and pathogens. This study highlights the role of these silent, latent viral infections that are totally asymptomatic," said Satya Dandekar, a lead researcher.

CMV is a common virus that infects as many as 90 per cent of adults in Africa and 70 per cent in the U.S. and Europe. However, researchers have labeled CMV to be not dangerous, except for those with compromised immune systems.

While the vast majority of CMV infections are subclinical, that does not mean the virus is inert.

Researchers found that animals infected with CMV had higher levels of Firmicutes and other butyrate-producing bacteria.

Butyrates are short-chain fatty acids that reduce inflammation but may also boost genes that help CMV persist in the body.

Infected animals also showed increased lymphocytes and cytokine-producing (inflammatory) T cells. These differences leveled off when the animals were moved indoors.

CMV infections generally increase immune activity but also diminish antibodies responding to influenza vaccination.

"There's a high degree of variation at the population level of how people respond to vaccines, and all the factors that contribute to these variations are not fully understood. Our paper shows the subclinical CMV infections may be one of the issues that contribute to that immune variation. This opens a new opportunity to come up with novel approaches to optimize and position the immune system to have higher quality responses to vaccines." Dandekar further said.

Researchers said that more work should go into understanding how the CMV reacts to a vaccine.

The study appears in the Journal of Virology.

(ANI)