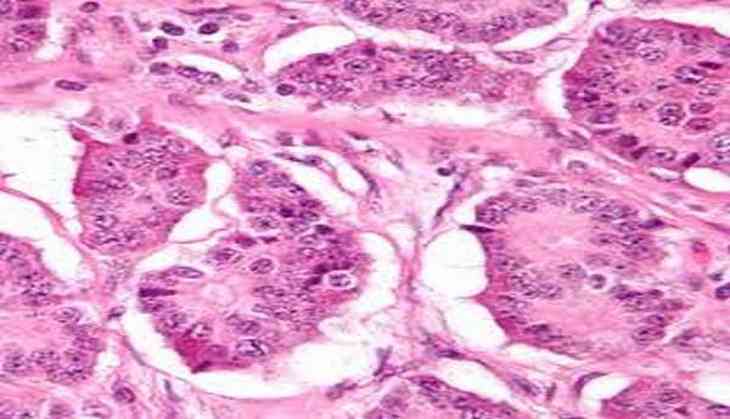

A study has found that patients with neuroendocrine cancer may experience fewer symptoms and survive longer by undergoing personalised peptide-receptor radionuclide therapy (PRRT).

PRRT has become a treatment of choice for relatively rare and easy-to-overlook neuroendocrine tumors ( NETs).

The targeted treatment is designed to home in on and attach to peptide-receptor positive tumors, while sparing tissues that might otherwise be damaged by systemic treatments.

Study author Jean-Mathieu Beauregard from Universite Laval in Quebec City, Quebec, Canada said that so far, the majority of PRRT treatments have been administered one-size-fits-all, meaning every patient receives about the same amount of radioactivity.

Beauregard added that many patients may not draw the maximum benefits from PRRT because they end up receiving a lesser dose than their body can realistically tolerate.

The team used a PRRT called lutetium-177 (177Lu)-octreotate, which mimics the somatostatin growth-inhibiting hormone.

Ordinarily, patients receive a fixed amount of radioactivity, such as 200 millicuries, in several sequential cycles.

This marks the first time that 177Lu-octreotate PRRT has been matched to the patient's individual tolerance based on finely tuned SPECT dosimetry that evaluates how much radiation is building up in key organs like the kidneys.

A total of 27 neuroendocrine cancer patients underwent 55 personalised 177Lu-octreotate cycles from April to December 2016, followed by quantitative SPECT dosimetry.

Radiation dose was quantified for the kidneys to optimise the administered amount of radioactivity, while remaining were safe and well tolerated by patients.

The side effects were recorded and blood counts, as well as renal and hepatic biochemistry, were performed at two, four and six weeks after each cycle of treatment.

The results showed an increase in the radiation dose to tumors for a majority of participants--increases as high as three times the dose delivered with conventional PRRT.

Furthermore, serious side effects and toxicity remained infrequent with the personalised approach.

Additional research is planned for the coming months to determine how personalized PRRT results in improved therapeutic benefits, such as reduced tumor progression and longer survival.

The study is scheduled to be presented at the 2017 Annual Meeting of the Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging.

A study has found that patients with neuroendocrine cancer may experience fewer symptoms and survive longer by undergoing personalised peptide-receptor radionuclide therapy (PRRT).

PRRT has become a treatment of choice for relatively rare and easy-to-overlook neuroendocrine tumors ( NETs).

The targeted treatment is designed to home in on and attach to peptide-receptor positive tumors, while sparing tissues that might otherwise be damaged by systemic treatments.

Study author Jean-Mathieu Beauregard from Universite Laval in Quebec City, Quebec, Canada said that so far, the majority of PRRT treatments have been administered one-size-fits-all, meaning every patient receives about the same amount of radioactivity.

Beauregard added that many patients may not draw the maximum benefits from PRRT because they end up receiving a lesser dose than their body can realistically tolerate.

The team used a PRRT called lutetium-177 (177Lu)-octreotate, which mimics the somatostatin growth-inhibiting hormone.

Ordinarily, patients receive a fixed amount of radioactivity, such as 200 millicuries, in several sequential cycles.

This marks the first time that 177Lu-octreotate PRRT has been matched to the patient's individual tolerance based on finely tuned SPECT dosimetry that evaluates how much radiation is building up in key organs like the kidneys.

A total of 27 neuroendocrine cancer patients underwent 55 personalised 177Lu-octreotate cycles from April to December 2016, followed by quantitative SPECT dosimetry.

Radiation dose was quantified for the kidneys to optimise the administered amount of radioactivity, while remaining were safe and well tolerated by patients.

The side effects were recorded and blood counts, as well as renal and hepatic biochemistry, were performed at two, four and six weeks after each cycle of treatment.

The results showed an increase in the radiation dose to tumors for a majority of participants--increases as high as three times the dose delivered with conventional PRRT.

Furthermore, serious side effects and toxicity remained infrequent with the personalised approach.

Additional research is planned for the coming months to determine how personalized PRRT results in improved therapeutic benefits, such as reduced tumor progression and longer survival.

The study is scheduled to be presented at the 2017 Annual Meeting of the Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging.

-ANI