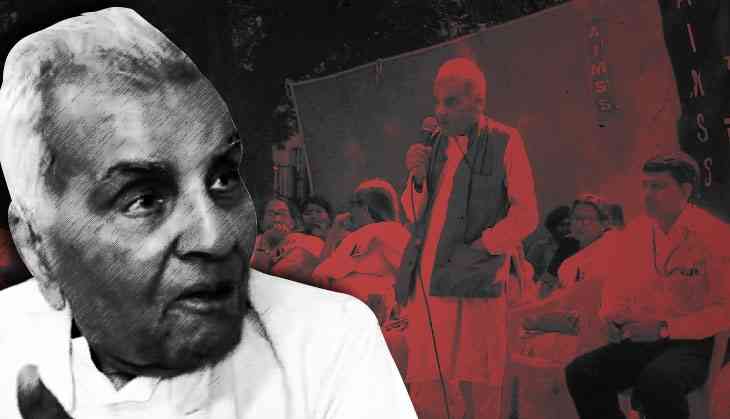

Rajindar to his close friends, Sachar Sahab to many, Justice Sachar was to the Manor born. Scion to an illustrious Hindu Punjabi family from Lahore in pre-partition India. He became a life-long socialist in his youth.

The West Punjab, now Pakistan's Punjab province gave to post-partition India some fine human beings and committed democratic socialists. Seared by the memory of the killings, mayhem and exodus, they kept their basic humanity, secular and Socialist beliefs intact.

Some of his lifelong colleagues were individuals like Prem Bhasin, stalwart of the Socialist movement in India; Hans Raj Gulati, a former MLA from Bannu in the North West Frontier Province (NWFP) and a senior functionary of the socialist Hind Mazdoor Sabha after Partition; Brij Mohan Toofan, President of the Socialist Party in Delhi until 1977; Ishwar Das Khanna and so many others.

His brother-in-law, veteran Journalist Kuldip Nayar, who survives Justice Sachar though not a formal socialist as the others were, was hewn out of that same earthy wisdom, the deeply humane Punjabi stock.

It was this intimate knowledge and affinity of the Muslim psyche that led to the crowning achievement of his life. As Chairperson of Prime Minister’s High Level Committee On Status of Muslims, popularly known as the Sachar Committee, he gave the lie to the vicious propaganda of the Hindutva right that minorities in India were mollycoddled.

Its implementation, scuttled presently by the ruling dispensation, has most of the answers to building a composite Indian identity in a few generations. You cannot deny minorities their share of the economic and social cake in India was his constant refrain both in public and private.

His economic philosophy was influenced by his deeply held socialist beliefs. Appalled by the robber barons many of whom masquerade as captains of Indian Industry, he bemoaned the lack of successive governments of adherence to Article 39 of the Indian Constitution, which stated that the State shall ensure, “that the operation of the economic system does not result in the concentration of wealth and means of production.”

He bemoaned that the fact that the Indian State should invest large sums of public money in non-performing and sick private capital ventures, bringing them back to health and then, horror of horrors, return it back to private management. He reminded those who cared to listen that this alone justified Marx’s taunt that “the State is the Executive Committee of the bourgeois class”.

Apart from his deeply held socialist views, his chairmanship in 1977-78 to review the Companies Act and the Monopolies and Restrictive Trade Practices Act produced a monumental report that is yet to be implemented in full.

His work on the composite identity of Punjabiyat in cooperation with former Prime Minister Inder Gujral, Kuldip Nayar, Patwant Singh, Dr Amrik Singh has not got the due it should have to put a balm on the hurt Sikh psyche in the aftermath of the anti-Sikh pogroms and the attack on the Golden Temple.

He was also concerned about the demise of Kashmiriyat. An identity that had been forged by Sheikh Abdullah, Prem Nath Bazaz, Mir Qasim and many others who sought to build a “Naya Kashmir”. An identity that was dead on arrival thanks to the back-room machinations of the security establishments in India and Pakistan.

His last personal and substantive conversation with me was over a year ago on the human rights situation in the Valley. He bemoaned with me the usage of pellet guns against unarmed demonstrators, yet saying that he had no time for those who sought enosis with Pakistan. The answer for him lay in Kashmiriyat. and the going back to the possibilities offered by the back-channel talks between Dr Manmohan Singh and General Musharaf.

As president of Peoples Union for Civil Liberties (PUCL), his campaigning against Terrorist and Disruptive Activities (Prevention) Act and Prevention of Terrorism Act was tireless.

Soon after his handing over his office as president of PUCL, he put a lot of energy in trying to revive a broad socialist movement in the country until the day he died.

Few know that before he was appointed to the Delhi High Court as an Additional Judge in 1972, he consulted Madhu Limaye and George Fernandes about the offer of the elevation to the Bench. He was keen to contest a parliamentary seat in the Punjab on a socialist ticket. He was told that his chances of being elected were as slim as finding the Holy Grail.

The Socialists and the country lost a chance in having a thoughtful Parliamentarian. However, the country gained in a having a fine judge, civil libertarian and humanist.

Diminutive in height, stooped in latter life by all the public burdens he willingly took on, he was long in stature and deep in heart. We will miss him.

The author is with the South Asia Human Rights Documentation Centre

Edited by Joyjeet Das