Fair pay for fair play: It's time for women's equality in sports

_1_59005_730x419-m.jpg)

When the US' Brandi Chastain celebrated by taking off her shirt after scoring the winning penalty in the 1999 Women's World Cup final, her celebration marked a new era in women’s sports. For almost 25 years, the US Women's National Team (USWNT) has dominated their field, consistently ranking in the top two women's football teams in the world. In contrast, their male counterparts had their best finish of third place in the inaugural World Cup in 1930, a feat they haven't come close to repeating since.

However, on 31 March, 2016, scarcely a year after winning their third World Cup, five prominent players of the USWNT – Hope Solo, Carli Lloyd, Becky Sauerbrunn, Alex Morgan and Megan Rapinoe – filed a federal complaint accusing the U.S. Soccer Federation of wage discrimination. The case was submitted to the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.

On 5 April, 2017, the US Women’s Soccer National team finally reached a new labour deal with U.S. Soccer, after more than a year of fighting for equal pay. The team was finally granted substantial raises, including a 30% increase in base pay and better bonus for individual pay.

Things have changed now, and, when the deal was struck, the players celebrated, but equal pay has still not been granted. This is because, just like at any other workplace, in any other profession and any other sport, only humans with one ‘X’ chromosome are entitled to higher earnings. Appease the women by offering a little bit more, and keep them at bay for a few years; when they protest again, rinse and repeat this winning formula. Tick tock. It works like clockwork.

The US football wage gap

Few national teams in football, men or women, have sparkled on the pitch as extraordinarily as the USWNT. With three World Cups and four Olympic gold medals, it isn’t difficult to guess why the players were complaining about not receiving the same incentives as men. Despite their achievements, the players of the women’s team have consistently been made to feel inferior next to the men’s team.

The USWNT already earned more than the men in terms of base salary. However, a heavily skewed bonus structure meant the men would out earn the women even if the women had their best season while the men had their worst. They would get paid after a match regardless of a win or loss; the women were always on a salary-based contract.

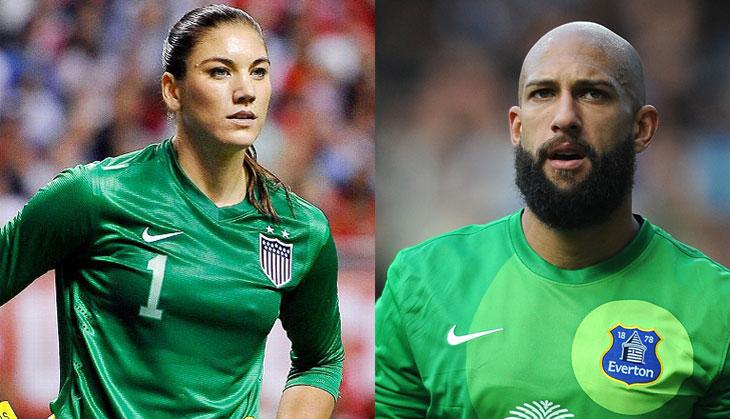

This is something the women themselves wanted, for the sake of security. However, this meant huge disparities in the pay scale. In 2015, a World Cup-winning year, Hope Solo was paid about US $366,000 in total by U.S. Soccer. In 2014, also a World Cup year for the men, team USA goalkeeper Tim Howard was paid $398,495. Solo played in 23 games for her country, while Howard played in 8. Does the men’s team deserve to get more for performing both less as well as worse?

Sexism over fairness

“I don’t want to use the word deserve in any of this,” Sunil Gulati, the president of the U.S. Soccer Federation, told Sports Illustrated when quizzed on the matter, “I’d reverse the question: Do you think revenue should matter at all in determination of compensation in a market economy?”

The USWNT continues to argue that they continue to produce the higher share of income for the governing body. In the 2015 Women's World Cup Final, an estimated 25 million people watched Carli Lloyd score three goals and seal a huge win against Japan. It remains the highest rated (and watched) soccer match watched on US television for both men and women, including the very popular European league games (It is more than the number that watched the 2015 NBA Finals championship game featuring Stephen Curry and LeBron James). People do tune in to watch the women’s team because they are brilliant.

In 2015, they brought in more than US $23 million in game revenue, about US $16 million more than the federation had projected. After expenses, the women turned a profit of US $6.6 million in 2015, while the men generated a profit of under US $2 million.

Was it an anomaly? Perhaps. Regardless, it shows that women athletes can be moneyspinners because they are as good, and in this case even better than the men.

Despite all of this, the USWNT has had to fight the U.S. Soccer Federation over sub-par treatment across an array of issues. One of their biggest complaints was being asked to play on hazardous AstroTurf instead of on grass. Conditions on AstroTurf have been so bad that it's led to game cancellations and strike threats among women’s teams. Effectively, women's sports also means poorer working conditions.

The situation in India

Unlike Indian Football, where national contracts don’t exist for the men’s and women’s team (but per diems and other incentives still have massive discrepancies), players in the Indian Cricket Team enjoy lucrative national contracts. When the Women's Cricket Association of India merged with the BCCI in 2006, women cricketers hoped the move would result in some positive changes.

However, it was only in November 2015 when the BCCI issued national contracts for women, while the policy was in place for the men’s cricket team since 2001. The highest salary a woman can earn playing for the Indian team is 15 lakhs a year - rewarded to a 'Grade A' player. In sharp contrast, a 'Grade C' player in the men’s team warrants a 'retainer fee of Rs 50 lakhs.

Shardul Thakur, with no international caps for India earns 50 lakhs a year and has a Grade C contract, while Mitali Raj and Jhulan Goswami, who have been playing for India for 15 years now, earn 15 lakhs a year.

A global problem

In the latest Deloitte Annual Review of Finance, it was proved that, on average, male footballers in England, home to the highly glamorous Premier League, earn more than three times what a female player gets paid in a year in just one a week.

Recently USA Hockey and its women's national team threatened to boycott the world championship if they didn’t receive better compensation. The Irish women's national soccer team also threatened to boycott an upcoming international match because of a labour dispute, claiming they aren't compensated for time off from their daily jobs. They say they don't even have their own team apparel, but instead share it with Ireland's youth teams.

The gender pay gap exists pretty much everywhere and across all sports; however, it has always been justified by claiming women’s teams are not as good as men’s, and that women’s sports are not as popular as the men’s. As shown by the USWNT, even these reasons don't necessarily pass muster.

While it would be erroneous to deny that globally men’s soccer is more popular and profitable than the women’s game, the extent of the skew between men's and women's football is still staggering.

To put things in simple figures, when Germany won the World Cup in 2014, FIFA awarded them $35 million. For getting knocked out in the round of 16, the US men’s team was awarded $9 million by FIFA. A year later, when the US women won the World Cup, the U.S. Soccer Federation received US $2 million from FIFA. Of course, the money the federation receives from the higher governing body plays a massive role in determining the pay too, and FIFA is therefore also complicit in this wage disparity.

Things don’t just stop at equal pay. Other conditions have repeatedly made women athletes second-class citizens. In the ICC World T20 held in India in 2016, women cricketers were made to fly economy while the men flew business; received a lower per diem than their male counterparts, and had a significantly lower winner fee. These complaints have also been made by women in different sports, from football to athletics.

A historic issue

History has evidence of women being unwelcome in the realm of sports. In 1896, Pierre de Coubertin, who founded the modern Olympic Games, described women’s sport as “the most unaesthetic sight human eyes could contemplate”. In 1921, the Football Association in England deemed the game “quite unsuitable for females”, and banned its clubs from loaning pitches to women.

Only in 1998 did the Marylebone Cricket Club, the custodians of the hallowed Lord’s Cricket Ground, lift its ban on female members. Only a month ago, the Muirfield Golf Club, one of Scotland’s oldest and most celebrated courses, passed a decision allowing women to become members.

The pay gap persists across all races, education levels, geography, and occupations. It is only in tennis where the popularity is even, and, at times, even trumps the men. And even there, equal prize money took decades of activism, notably by Billie Jean King, and yet it still remains controversial.

Changing sexist mindsets

The question eventually is ethical. Equal pay for equal play. Sadly, this entire episode with the USWNT is only an exasperating reminder that despite everything women do on the pitch, even when they outperform their male counterparts, excuses or “justifications” can always be given and the buck will be passed.

The justifications too are absurd, because the entire problem is cyclical. Federations, associations, and governments say that women don’t attract revenues and hence they can’t fund women's teams as well as men’s. This results in fewer opportunities for women to play sport, inadequate coaching and facilities compared with those enjoyed by men, and meagre salaries, even for playing international sport, which damages the quality of a game. The obvious result of this is that the women's game, naturally, loses its attractiveness. Then we complain that women’s sport is not as glamorous and marketable as men’s, and the cycle repeats itself in perpetuity.

Lack of equal pay between the genders is a deep-set and universal problem that requires a change in mindset before any of the changes can transcend into budgets and laws. Until there is an underlying shift towards gender equality across society, women in sport will always be treated as underpaid second-class citizens. Women need to be invested in, and their contribution and capabilities demand equal respect, equal treatment, and equal compensation.

Eventually, equal pay isn’t just a women’s rights issue; it’s a human rights issue.