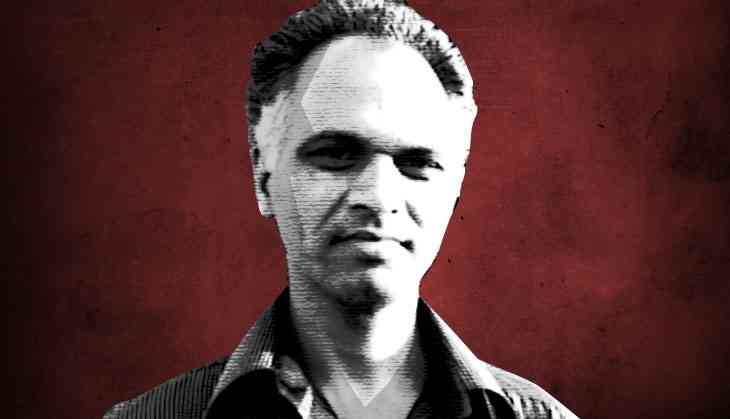

Why activists like Sudhir Dhawale are seen as a threat by the BJP govt

The arrest of Sudhir Dhawale, Surendra Gadling, Shoma Sen, Rona Wilson and Mahesh Raut in the Bhima-Koregaon case by Maharashtra Police under the draconian Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, has stunned the civil society. They have been termed as 'urban' or just plain Naxalites for the ever gullible self-styled nationalists and their arrest would form a part of the political debates where nationalism is the flavour.

Whether the allegations against them stand the scrutiny of law remains to be seen as the matter unfolds in the courts but one needs to ponder how and why these people are considered to be outlaws by the ruling dispensation.

Of those arrested, this writer had an opportunity to interact with Dhawale apart from meeting him when he was in Punjab to participate in a civil society initiative to discuss the possibility of the coming together of the Left and Dalit forces in the country.

It was during the course of interaction that this reporter realised that people like Dhawale are the ones who are capable of mobilising the marginalized communities on a large scale in small mofussil towns and villages where some of the most gruesome atrocities are recorded.

They are the ones who give a direction and voice to the victims who are quite often illiterate or semi literate at the most. They are the ones organising movements where top Dalit leaders like Mayawati, Ram Vilas Paswan or even the likes of Udit Raj are never to be seen. They are people who do not mince words when asked direct uncomfortable questions and are candid in their response. In short they are not politicians but plain activists.

During the interaction, Dhawale who represented Republican Panthers Jati Vinash ka Andolan had given a copy of a bilingual journal 'Vidroh' that he was bringing out. The cover had carried the words 'Kisi ke Baap ka Hindustan Thode hi hai' and this was enough to gauge that he stood for a society that is inclusive.

He was candid in saying that he was a part of an initiative since the Khairlanji massacre of 2006 where four Dalits were killed allegedly by the members of the dominant Kunbi caste in Bhandara district of Maharashtra in 2006. This initiative aimed at bringing together radical Left activists and Ambedkarites for the common cause of social justice.

“We believe that the atrocities cannot be removed by the state machinery and the Dalits need to stand up for themselves. Dalit movements have been continuing on the ground especially against atrocities especially in small towns and cities. You do not get to know about them because the mainstream media never reaches there. It is also true that it is not in a planned manner,” he said. He pointed that since the so-called Dalit parties fail to provide them the leadership whenever there is an attack on the Dalits, the people are left with no choice other than taking to the streets in the name of Babasaheb Bhim Rao Ambedkar.

He was of the view that the Dalit issues in India eventually boil down to issues of class and that is why Ambedkar did not only talk about the identity and respect of Dalits but also took forward the issues related to the farmers and labourers. “His approach was also radical. Ambedkar experimented with the parliamentary politics and was instrumental in drafting thee constitution but he could not give it the shape of an instrument of state socialism because the drafting committee again was dominated by the landed castes and capitalists. He could not get the Hindu Code Bill passed and returned to the path of struggle,” he pointed.

Dhawale pointed that the shortcoming of Left in India is that while it talks of the proletariat, it fails to address the issues of the caste of the proletariat in the villages. He was of the view that since the issues of caste and class are to be addressed together, the Left forces and the Ambedkarites need to work in tandem simultaneously.

“If the Left talks of the proletariat revolution, the proletariat in the villages is mostly Dalit. That is why the squads of the extreme left or Naxalites were first constituted in the villages and they took shelter there. Their base was among the Dalits and they led the fight on the issue of Dalit self-esteem and land rights. Dalits also rose in the ranks of Naxal groups and if someone has given a befitting reply to the upper caste militia in India like Ranveer Sena it is the Naxalites,” he explained.

“We are not talking about bringing together the Marxist and Ambedkarite ideology. They are different streams of philosophy. But they can join hands for public good,” Dhawale underlined.

He had a different take on the RSS working among the Dalits on one hand to lure them and the increasing attacks on Dalits in thee name of cow vigilantism and religion particularly in the state ruled by the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). “This is the double face of theirs. They want a vote bank but do not want to address the economic concerns of this vote bank. If you do not want to address their concerns you need to bring in the issues of cow and religion. They need Dalits to act as their militia,” he said.

On the issue of no major Dalit leader emerging at pan India level, he said that this is because of the diversity of the country. But at the same time he pointed that local agitations and movements have thrown up leaders like Jignesh Mevani, Prashanth Dontha and Chandrashekhar Azad 'Ravan'.

Dhawale's book on the 'institutional murder' of Rohith Vemula made waves. He said that slogans like 'Jai Bhim Lal Salam' should not be election oriented. The Left that leads on issues on economy needs to lead on issues of caste also.

Dhawale had got a rousing response to his address at Mansa which is seen as a cradle off the Left in Punjab where issues of Dalit identity and strategy of the Left was discussed threadbare. Dhawale remains behind bars but the issues that he raised remain very much alive in the public domain.