Meet the Bantania, eastern UP's forgotten community of teak foresters

Nearly 20 km from Gorakhpur, the nerve centre of Poorvanchal or Eastern UP, around 40,000 people in 23 villages are still living without paved roads, hospitals, schools and power – the basic amenities any state should provide its citizens. This marginalised community is locally known as the Bantania.

As the car hits National Highway 28, the stretch between Gorakhpur and Maharajganj, a thick forest of teak, which the locals call Sakhu, suddenly appears on both sides, almost out of nowhere. Neatly lined trees on both sides of the highway tell their own story – that it's not a natural forest but organised plantation.

The teak plantation was developed by Bantania, the Dalit community. And how they came to be known as Bantania is an interesting story in itself. The moniker is made up of two words, 'Ban' and 'Taungya'.

Also Read: Eastern UP’s encephalitis epidemic lies forgotten in the din of the election

Ban, of course, is the Hindustani word for forest. In the old days of the Raj, the British used a particular technique for developing plantations in Burma called 'Taungya'.

In the 1920s, when the railway arrived in Gorakhpur, it required an enormous amount of wood for sleepers. To ensure constant supply, the British employed members of the local community to plant teak, using the Taungya technique.

The Bantania have been dependent on these “forests” since. As wages, the British gave them a piece of land around the plantations for cultivation. This ensured they remained tied to the system. There are still many settlements of the community in these “forests”. After the British left, the Bantania took up farming as their primary occupation, planting teak only during the monsoon.

The teak forest on either side of NH 28 between Gorakhpur and Maharajganj, is what has grown out of the work of four-five generations of this community. The plantations now cover roughly 55,000 acres of land.

Eighteen of the 23 Bantania villages fall in Maharajganj, while the rest are in Gorakhpur. The community numbers around 40,000, of which around 21,000 are eligible voters.

Abandoned by their own

After the British left and India embraced democracy, the Bantania continued to plant teak. In the 1980s, however, the laws governing forests became more strict as the government sought to take control of these areas. And like most other forest-dwelling communities in the country, the Bantania were treated as a threat by the forest officials.

Soon, they were barred from collecting firewood or any other forest produce from the plantation they had laid and nurtured for decades. All they could do was cultivate the land given to them by the British while all other traditional activities linked to the forest became criminal acts under law.

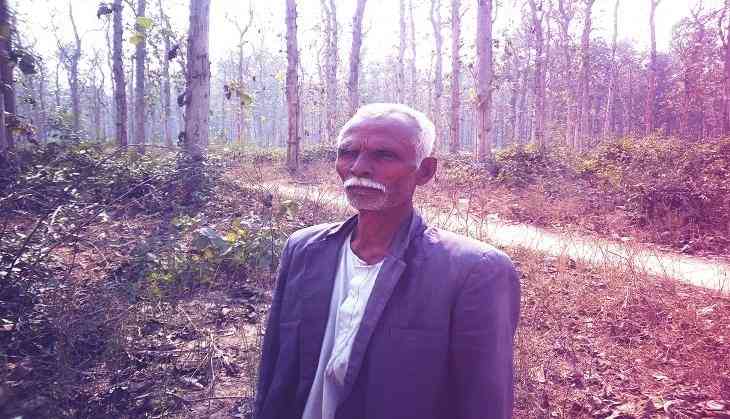

This situation of his community anguishes Chaudhary Devi Prasad, a Bantania from Rajai Kale, no end. “This huge forest was planted by our forefathers. Now, the forest department does not allow us to take out even a twig,” he says.

Devi Prasad adds, “The forest department was envisioned to develop the forests. But since they barred us, not even one acre of new forest has been added.”

Also Read: Nishad Party: Why Gorakhpur's river communities could drown SP, BJP & BSP

There's more to their plight. Since the land they cultivate is in the forest, the government has declared the Bantania settlements as “non revenue villages”. This deprives them of government schemes that other villages are entitled to.

It was only in 1995 that the Bantania got the right to vote in assembly and parliamentary elections. And it wasn't until 2015 that they were allowed to vote in panchayat election. Getting voting rights made them hopeful that it would finally help bring basic facilities like electricity, schools, dispensaries, drinking water to their settlements.

That did not happen.

Every time there is some movement on getting these facilities, the forest department creates hurdles on the pretext that these settlements are in the middle of the forest. Even the politicians who visit them occasionally use opposition by the forest department as an alibi.

Devi Prasad explains, “Yogi Adityanath has visited twice and promised development in our villages. Nothing has come of his promises so far,” he says, pointing to a power line a few hundred metres away. “It is barely 100 metres from my house, but we still can’t use it.”

This election, Devi Prasad says, only a Samajwadi Party leader has come visiting so far. And he did not discuss their issues.

Who's to blame for the Bantania's plight?

Are the local representatives helpless? That doesn’t seem to be true. Since the Forest Rights Act, 2006, was enacted, it has become easier for forest dwelling communities to use forests for livelihood. While forest dwellers in other parts of the country have used this law to their benefit, the local representatives here are either clueless or unwilling to improve the lives of the members of this community.

As Manoj Singh, a cultural activist in Gorakhpur who also organises a film festival titled ‘Cinema of Resistance’, explains, “It is not difficult to extend the basic facilities of power, roads and water to Bantania villages. It can be easily done if Adityanath, the local MP, takes the initiative. But politicians want to keep the issue unresolved, perhaps.”

Also Read: UP polls: Why Yogi Adityanath's double game will prove costly for BJP

First published: 3 March 2017, 22:39 IST