Born in a limbo: This photographer is set to show the statelessness of Rohingya newborns

For Dhaka-based photojournalist Turjoy Chowdhury, the Rohingya refugee crisis was nothing new. In fact, having photographed the situation as it unfolded in his native Bangladesh, Chowdhury was used to taking pictures in and around Cox's Bazar, the largest Rohingya refugee camps in the country.

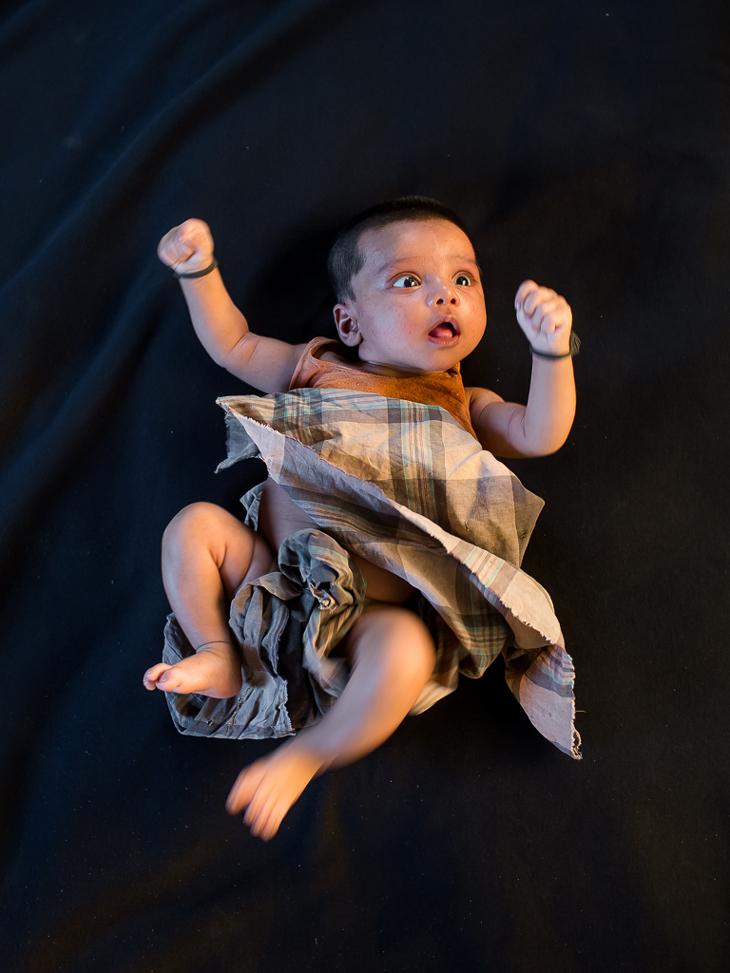

However, during one of his regular visits to the camp where Chowdhury covered the daily life of refugees, he suddenly heard the sound of a baby wailing amidst the everyday din. He traced the crying to a makeshift shelter. Inside, he discovered the source of the sound – a day-old baby. “At that moment, I experienced a feeling that I cannot explain in words,” Chowdhury reveals. “The mother was from Myanmar and the baby was born in a refugee camp in Bangladesh with only one identity – refugee.”

As he began to photograph the child, the mother uncovered the baby, removing the blanket provided by relief aid authorities and asking Chowdhury to take a good picture. And, thus, thanks to a serendipitous accident, was crafted Chowdhury's moving portrait series, Born Refugee.

Refugee by birth

Remembering that moment, Chowdhury thinks back to seeing the baby’s face through his camera's viewfinder. Despite the chaos and despair around him, he couldn’t help but focus on her innocent face. “I was asking myself, 'where is the word “refugee” written? or 'Religion'? She is just like any other innocent baby in this world. Then why would she remain stateless life-long? Why does an infinite uncertainty await her?” he recounts.

According to the Bangladesh Citizenship Act of 1951, a child born in Bangladesh to foreign parents cannot be a citizen of the country, either by birth or by descent. Similarly, the Myanmar Citizenship Law of 1982 does not recognise the Rohingya newborns as citizens either, since their parents have migrated to another country.

What’s more, barring a few who settled before 1823, the bulk of the Rohingyas are not even considered a national race in Myanmar. As such, they remain excluded from belonging by default.

“The consequences of being born and having a life in such limbo are horrible! They are most likely to be termed 'stateless', as neither Myanmar nor Bangladesh consider these newborns as their citizens,” says Chowdhury. These thoughts stayed with the photographer as he walked around the camps, causing him to narrow his focus from just life in the camps to documenting the camp's youngest and most vulnerable inhabitants.

All told, Chowdhury managed to photograph around 25 more newborns. While some were only a day old, others were as old as three months. His task was two-fold – handling the babies and also their mothers! “The most important and challenging thing was trust building since it’s kind of weird to ask any mother to give her child to a stranger, especially to a male photographer,” he says.

A blank future

Despite the innocence of the infants that he photographed, Chowdhury could not help but notice the poor conditions under which families in the camp lived. While most newborns suffered from malnutrition, their families were helpless to intervene as they were dependent on relief aid for survival.

“Honestly speaking, they don’t know what to do now and what’s going to happen in their future. Some of them want to be back in Myanmar only if they get security of life, while some want to stay in Bangladesh, but not like this. And when I asked about the future of these babies, I saw them blank, completely blank,” he says.

In fact, a lot of the infants he documented did not even have names, the most basic of identifiers. In one instance, after asking the parents about the name of the baby, he was asked to wait by the parents, who had only realised in that moment that they had yet to think about a name for the baby.

“They called other relatives and friends and, in that very moment, they gave her a name just because I had asked and I was about to take her photograph,” he recollects.

Despite the crisis becoming more complicated by each passing day, Turjoy feels that there can be a way to deal with the ongoing situation. “In the short term, the immediate necessity is providing basic facilities that will help them survive,” Chowdhury says before adding, “But again I am saying that this cannot be a solution. This is just a temporary support to deal with the extreme moment.”

As he continues to work on the project, he hopes to make many more portraits and highlight the extent of the refugee crisis all over the world. And while it has become a watershed moment for Chowdhury's visual journey, one can only hope that the awareness his series raises will help improve the futures of the infants he photographed.

For more information, visit www.turjoychowdhury.com