Vikramaditya Motwane is looking at books for the next big Bollywood hit

Largely known for the Mumbai Film Festival, the Mumbai Academy of Moving Image (MAMI) is also constantly looking to help evolve Indian cinema. As part of their effort, MAMI has started a new initiative – Word to Screen – meant to bring together the worlds of publishing and cinema, to foster book-to-screen adaptations.

This niche, grossly under-utilised source in modern Indian cinema, is a potential goldmine MAMI is hoping to unlock. While the first edition of the program saw a number of books shortlisted and pitched to content creators, with some even in development now, MAMI recently held a bootcamp for publishers to better prepare them for this year's edition.

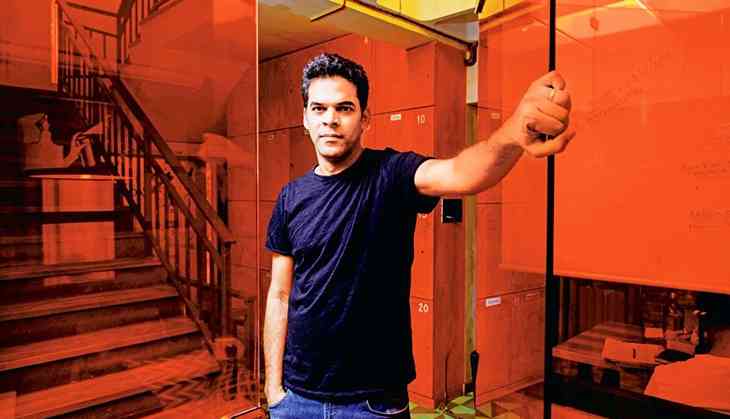

Appearing at the event, one of the rising stars of Indian cinema, director Vikramaditya Motwane, spoke to publishers and authors about the art of pitching their books to creators like him. After his session, Motwane sat down with Catch to talk about what got him involved with Word to Screen, the influence literature has had on him, as well as issues currently plaguing Bollywood like nepotism and censorship.

These are the edited excerpts:

Ranjan Crasta (RC): Your association with MAMI is known, but what about the Word to Screen initiative sparked your interest?

Vikramaditya Motwane (VM): While I've been part of the MAMI board for a few years, it's also my home festival and I'm extremely passionate about it, so obviously, anything for MAMI. But what also got me interested is that as a writer-producer-director (and I'm actually wearing all those hats pretty much all the time) you find that one of the things that is always lacking are quality stories.

So much of that can, and should come from books. Sure, not every book can be made into a movie, and not every good book makes a good movie, but there's a lot of source material here. If you adapt it the right way, there's a lot of great material out there.

Selfishly, from the point of view of a writer-producer-director, I just want better movies, which is why I'd like to tap into this very large market of literature.

RC: How important a role has literature played in your creative process?

VM: It's played a big role, I mean, I can't quantify it and say specifically it's this, this, and this, but the stuff you read definitely has an effect. You get involved in the story-telling, you get involved in the mysteries, and develop a love for reading.

The tone you start to pick up from books later on, the authors that you like to read, manifests subconsciously in your work, and shapes your visual vocabulary. I personally feel very influenced by Raymond Chandler, for example.

RC: None of your directorial ventures so far are based on books. Are you actively looking at maybe adapting a book to the big screen?

VM: You're right, they haven't been based on literature. I mean, Lootera was loosely based on a short story, The Last Leaf, but other than that, no. Currently, I'm not actively looking to adapt a book to the big screen, but I'd love to. We're [Phantom Films] doing an adaptation of Sacred Games, which is a challenge because it's a 1000-page book.

RC: What attracted Phantom Films to the Sacred Games project?

VM: Just the book itself. Vikram Chandra has written a book that is deep, it's fast, it's got very compelling characters and a great mystery at its core. It also had a great pitch.

We have a tendency as producers, and this was something I used to hate as a young film-maker, to ask for one-line pitches. But you realise as you get more experience that it makes sense, because it simplifies your book to a pitch, and that's what's going to get people interested in the story. I think we don't give enough credit to the idea of a one-line pitch for a story.

Sacred Games has a great pitch, and a great idea that intrigues you into asking'Oh, then what?' That is what you want when you tell anyone about any story, because that curiosity will make people watch it.

RC: In the West, book-to-screen adaptations are fairly common, whereas in India this seems far less common. Why do you think this is the case?

VM: That's a good question, and I'm very curious to know what the publishing side has to say. I may be wrong, but it could be because of a lack of trust in the film industry. Maybe, so far, because the industry just steals stuff, and there have been no checks and balances really in the industry. So this coming together really hasn't happened very much.

RC: Do you see this becoming more common in a market place where originality is scarce?

VM: Absolutely, I think this is the need of the hour. On both sides, publishing and cinema. Yes, there is a certain amount of looking down on the film industry from the publishing or literary point of a view. But I think that even if a certain percentage of book writers decide to write a book to be able to turn it into a screenplay, I'm all for it. It gets more writers out there, more stories out there, and that can't be bad.

RC: Even though many books are picked for screen adaptations, very few of these projects actually come to fruition. Why?

VM: Production houses do not have the resources right now to go and read through every book and work on the screenplays. Nor are there enough agents and middlemen to do this either.

I think, ultimately, the gap comes down to passion. It comes down to one's person's passion to chase something to the point where you can get a screenplay ready. It's not so easy to turn a book into a screenplay. It's a journey, it's not overnight. You got take the book and break it down, refine a pitch, then a synopsis, then a treatment, and then a screenplay. This doesn't always happen.

RC: The current CBFC chief has issued a slew of ridiculous diktats, one of the more recent being that actors should not be depicted smoking or drinking on screen. How do you see this affecting creativity and story-telling in this country?

VM: It will impact creativity. I know many film-makers who just didn't want to deal with this little logo coming across your screen, and just decided they won't make their characters smoke or drink. Who wants to go through that trouble. I think something similar will happen now.

I don't think this will fly in court. Quite honestly, I think if you take this to court it's just going to be shot down. We chose an Udta Punjab to fight it, and we won. It's just a question of if you choose to go to the Film Certification Appellate Tribunal and the court to fight it. I personally think it's ridiculous, and I don't think it will fly.

RC: Big banner productions like yours are able to fight this, what about smaller creators with less resources?

VM: There's no way. They can't fight it. We fought the Udta Punjab case, partly because the film warranted it, but also because we thought that if we set a precedent, it will make things easier for those who come after us.

The CBFC is smart in the sense that they know people apply for certification only once the film is ready, and you only have a limited time to fight them. So they can fight you for that time, and, because you only have limited time, you eventually have to agree to what they say.

Where is this going? I don't know. There's a larger question of where this society is going if the CBFC is a reflection of society.

RC: Recently at IIFA, the spectre of nepotism rose again. As someone who isn't from a Bollywood family, and who has done movies both with and without star kids, what are your thoughts on nepotism in Bollywood?

VM: It's the same with any other industry, there is always favouritism towards a certain kind of people. It's like asking why Akash Ambani is part of Reliance. It's the same thing.

I don't think you can point a finger at the film industry specifically, when a lot of it also has to do with the interest that the press themselves show in star kids. Nobody is telling Sara Ali Khan to go out and get their pictures taken, the fact is that her pictures are being taken.

The press have been hounding Saif Ali Khan and Kareen Kapoor for pictures of Taimur when he's just seven-months-old. So it's a bit of a double-standard for the press to then turn around and accuse the film industry of nepotism. It's a double-edged thing.

Look, I cast Sonakshi in Lootera because I thought she was great in Dabanng, so I thought she'd be great opposite Ranveer.

I cast Harshvardhan, selfishly, simply because that's the only way my film would get made because producers are more excited about producing a film with him in it. Then I auditioned him, and he worked for me.