Lucidly informative Coromandel, A Personal History... exposes Charles Allen's love for the Raj

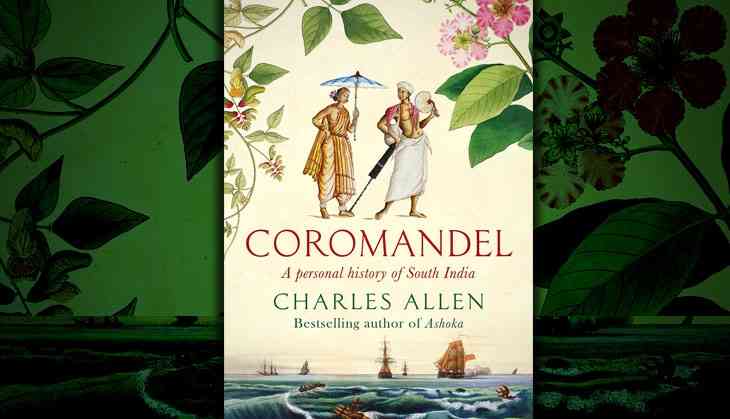

Title: Coromandel, A Personal History of South India

Author: Charles Allen

Publisher: Little Brown, 2017

As a devoted reader of Charles Allen, Coromandel, A Personal History of South India – his third book – overwhelmed me with its lucidity and depth of information. The facts of history have been so enchantingly woven that it is difficult to put the book down before one is through with it.

With Coromandel, Allen has widened the canvas to begin with the history of humankind, their travel throughout the formative years of the earth, the continental drifts to how it is today. Allen looks at the volcanic southern plateau, the land of Agastya, geologically the oldest, with two mountainous ridges in the east and the west (the Western and Eastern Ghats), much higher than the huge trough between the northern mountains. This today is the plains of North India, filled by the alluvial brought down by the glacier fed rivers of the north.

This was a land of peoples who spoke languages very different from the languages spoken by peoples in the north. In the chapter on Agastya’s country, Allen emphasises the pain and labour taken by the scholars of the East India Company to understand and unravel the mysteries of this unknown terrain. The College of Fort St. George in Madras (now Chennai) and the College of Fort William in Calcutta (now Kolkata) who relentlessly worked to decipher it.

It was Francis Ellis who ascribed the southern languages as ‘Dravidian’ languages. But his untimely death brought about another scholar Robert Caldwell into the scene. Caldwell acclaimed the ‘combined blessings’ of Pax Brittannica and Protestant Christianity for his monumental work, the Comparative Grammar of the Dravidian or the South Indian family of languages. He further assumed that Brahmanic/ Sanskrit intrusion into the south brought about caste rigidity and caste hierarchy.

Caldwell had a vigorous proselytising agenda among the Dravidian adivasis and lower caste people. This kindled a self-respect movement and eventually led to the rise in the Dravidian movement. Caldwell’s contribution to what is being called the Tamil Renaissance has been honoured with his statue being erected on the seashore of Chennai.

Along with this developed the idea of a lost continent. Allen endorses this idea of a long lost human settlement located off Kanyakumari. Interestingly he brings in the story of Lemuria along with an attractive map drawn from the imagination of some early writers. While in later chapters he pleads for rationalists like Kalburgi, Panesar who were killed in recent years, here his idea of a Tamil utopia defies rationality. Allen’s glorification of the Tamil renaissance and the subsequent Dravidian movement is constructed more to satisfy popular identity politics than based on historical evidence. He of course, by calling this a personal history, absolves himself from the critique of historians.

Allen has a special interest in the non-Brahmanical religious orders. The 5th century BCE saw the rise of several Nastika philosophical gurus including Siddhartha Gautama, Vardhamana Mahavira, Goshala Mankkhaliputta, Ajita Kesakambali, Purana Kasyapa among some. The word Nastika pointed out those philosophical thoughts which did not accept the authority of the Vedas.

Excepting Buddhism and Jainism, the others only survived for a few years. Both these orders denied the Vedic caste system and flourished among the lower castes with the patronage from the vyasyas, the trading caste. Buddhism developed into a well organised religious order when it received royal patronage from Magadh. Jainism on the other hand had only a few royal patrons. The Jain gurus with their unique lives of austerity and self-sacrifice continues to remain popular among a vast number of people.

The early Indian art and architecture still survive in the form of stupas and chaityas. Those bas-relief were the earliest evidence of art. The rock-cut chaityas and viharas were copied from early wooden examples.

With the rise of the Guptas, the Brahmanical religion received a new impetus and Brahmanic religious images swept over whole of India. It was a time for flourishing of art and literature. The classical era of art came to be adopted throughout the land with the best Ajanta frescoes being drawn using the classical norms set out by the Silpasastras, on one hand and the literature of Kalidasa and others on the other. Even the paintings in Sigiriya in Sri Lanka had the same stylistic approach of Ajanta.

After the Guptas there were smaller dynasties. The urban centres that flourished began to decline. Absence of coins in business transaction gave some credence to RS Sharma’s theory of feudalism. In the south, the Rashtrakutas were gaining an all-India role. The final transition to the powerful Chola state brought in a new phase of imperial power. Art and literature flourished. There developed regional varieties of the Gupta idiom - exquisite bronzes, gigantic temples.

Here interestingly Allen compares Chola imperialism with modern day imperialism: “The Chola Empire is something that Indian nationalists tend to overlook when they berate Britain for its imperialism!”(p255). This is a strange analogy and it gives an insight into Allen’s defence of his country of birth.

Allen meticulously mentions the pioneering works, mostly from the 17th century - even the marauders are given much credit for their observations. He mentions Niuehf, a Dutch, as the first person to mention the customs and costumes of the Nayars. Allen has gone as far as giving Tessitori, an Italian scholar, the credit of discovering the Indus Valley Civilisation and not to RD Banerji. The importance of the site of Mohenjodaro was realised by this officer and he informed Sir John Marshall of its importance (p377 note no.30).

Some scholars have marked the Dravidian south with the Brahmanic north on the basis of marriage and inheritance law. There is a strong linguistic difference between even the Tamil Brahmanas and, others, but they all still follow close-cousin marriage. “In theory, Dravidian and Indo-Aryan speakers adhere to two fundamentally different kinship systems. Dravidian kinship terminology is based on the cross-cousin marriage ..........By contrast in the Indo-Aryan marriage system exogamy of consanguines prevail..........” (The roots of Hinduism, The Early Aryan and the Industrial Civilization: Asko Parpola, Oxford University Press, 2015, p166). Allen has sifted the available material but not considered this aspect. This practice of cross-cousin marriage is still in use.

The book is outstanding for its use of old illustrations that provide an insight into the time that it depicts.

Post script: Allen at the end writes of his appreciation of the The Continent of Circe of Nirod C Chowdhury and his love for India. But, agreeing with Sashi Tharoor I would place him as one of most “unabashed(ly)” Anglophile and supporter of the British Empire. Browsing through ‘Orientalism’, in the very first page Edward W. Said states: “The Orient was almost a European invention, and had been since antiquity a place of romance, exotic beings, haunting memories and landscapes, remarkable experiences.” This resounded in this book.

References:

Orientalism; Edward W. Said, Vintage Books, New York, 1979.

An Era of Darkness: The British Empire in India; Shah Tharoor, Aleph Book Company, New Delhi, 2016.

The roots of Hinduism, The Early Aryan and the Indus Civilization; Asko Parpola, Oxford University

Press, 2015

History of Indian and Indonesian Art, A.K. Coomaraswamy, Dover Publications INC., New York, 1965.

The author retired as Professor of History from North Bengal University, specialising in Ancient Indian History and Archaeology.