'Frondeurs' and fake news: how misinformation ruled in 17th-century France

We are in the midst of a information revolution, matched perhaps only by the printing revolution of the 15th century and the reading revolution of the 18th. The digital revolution has made writers, commentators, and publishers of us all – and we can reach potential audiences of millions at the touch of a button.

This level of reach would have been unfathomable in the 17th century, when a thousand copies was considered a huge print run. However 17th-century readers faced some of the same problems we encounter today. The challenge of finding unbiased, accurate reportage of relevant political issues was as daunting in the 1640s as it is now. We are told we live in a “post-truth” era – which suggests that there has, at some stage, been a golden age of truth. In fact, consumers of news have always been subject to the perils of misinformation or propaganda – it’s by no means the first era of fake news.

Our media today combines more information with faster distribution than ever before. However, acceleration like this has happened previously in times of intense political upheaval. During the 1640s and 1650s Western Europe stumbled out of the Thirty Years War only to be plunged straight back into revolts, civil wars and regicide. During this intense period the medium of print was pushed to new limits. Across France and England, royalists, frondeurs (political rebels), roundheads and cavaliers faced off not just on the battlefield but through the art and wiles of the pamphleteer. They presented clearly antagonistic and contradictory versions of the “truth”, purposefully offering dramatically different views of their actions for or against the state.

French letters

In France, news travelled in a variety of ways – through pamphlets, affiches, which were posted around cities, and billets – small card-sized reports that could be hidden or discarded quickly in the event of arrest. Low literacy rates did little to slow the spread of this news, particularly in urban areas. News was relayed (and redrafted) often by word of mouth – the social media of the age. Colporteurs peddled songs and stories on the streets, often scribbled down on notes, or sung aloud to an already well-known tune. Making the message memorable was half the battle – the other half could be covered by the outlandish or scandalous nature of the material.

One of the best-known examples of seditious material during this decade was that of the Mazarinades during the French civil wars during the early years of Louis XIV’s reign. These pamphlets, primarily attacking Louis XIV’s prime minister Cardinal Mazarin, levelled charges of everything from corruption and treason to incest and sodomy and other sexual misdemeanours against the Italian cardinal.

The outlandish and extreme claims made by this particular set of pamphlets have echoed in the political sphere over the past year. Probably the best-known recent example of “fake news” was the Pizzagate case, in which a pizza parlour in Washington DC was targeted as a supposed hub of a paedophile ring led by high-ranking Democrats – leading to a shooting at the restaurant when one conspiracy theorist went to investigate further. This conspiracy theory shared a number of characteristics with Mazarin’s treatment, not least in that they both raised the issue of child abuse – conflating sexual disorder with political corruption is an old trick.

Not all readers were (or will be) misled. Many were exposed to a multitude of viewpoints, gaining a balance at least from a wider consumption of material, sometimes handed to them on the street, or simply listened to as they went about their daily business. Coureurs and coureuses (male and female “runners”) sang the latest news on the street and were hard to avoid – indeed these “songs-of-news” were better known as the original “vaudevilles”, literally “what goes around the city”. In the same way, any discerning internet surfer today can find a huge range of competing viewpoints – but the packaging of news online now presents a different set of problems.

Falsehood flies

Distinguishing between misinformation and disinformation is challenging. This leads to the charge of “fake news” being levelled at almost all outlets – Donald Trump’s habit of accusing the mainstream media of lying has become a particular feature of his administration. This raises an urgent question: if the political establishment continues to undermine the value of the press and to erode its integrity by lumping investigative journalism with unsubstantiated rumour, what measures to control freedom of expression and means of communication will government deem justifiable?

The latter decades of the 17th century were characterised by severe repression of the press, especially effective in Louis XIV’s France where many were persecuted for writing and publishing seditious material. Many fled the country, or published on the borders around France. In England rumour continued to weave political magic or havoc depending on one’s perspective, not least in episodes such as The Popish Plot in the 1670s – the widely believed “fake news” that Jesuits were planning to do away with Charles II in favour of his Catholic younger brother James – but it tended to be a much safer place to be a journalist or pamphleteer, despite considerable political and religious tensions.

The role of the press during this period certainly gave commentators cause for concern. Jonathan Swift displayed his usual healthy cynicism when he noted that: “Falsehood flies, and truth comes limping after it.” But we can also take heart from the 1644 work Areopagitica, Milton’s timely treatise on the importance of the freedom of expression:

For who knows not that Truth is strong … she needs no policies, nor strategems, nor licencings to make her victorious, those are the shifts and the defences that error uses against her power.

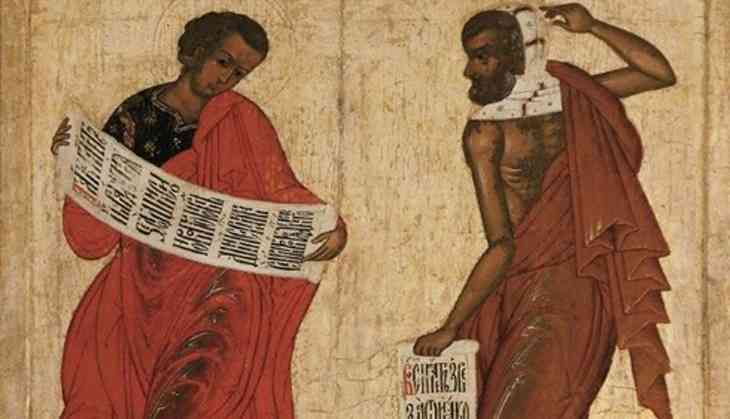

![]() The advice of that age endures now – let falsity and deception serve as unavoidable counterpoints to what is accurate. They underline the necessity of identifying what is fake, disputing what is wrong, and the imperative of pursuing the truth.

The advice of that age endures now – let falsity and deception serve as unavoidable counterpoints to what is accurate. They underline the necessity of identifying what is fake, disputing what is wrong, and the imperative of pursuing the truth.

Linda Kiernan, Lecturer in French History, Trinity College Dublin

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

First published: 2 August 2017, 15:37 IST