Decoding the music masterpieces: Bach’s Six Solo Cello Suites

Johann Sebastian Bach’s Six Solo Cello Suites are some of the most iconic classical music works. They have inspired not only cellists and audiences but other artforms as well, and they have been featured in ballet and theatre productions, even in films.

In Peter Weir’s Master and Commander (2003), Jack Aubrey’s (Russell Crowe) first sighting of the Galapagos Islands is accompanied by the Prelude from Suite I.

It is intriguing to consider what might have turned Bach’s interest towards an instrument he was not known to have played. After all, in the first three decades of his life (he was born in 1685), his artistic interest focused almost without exception on pieces that he would have either performed from a keyboard or directed, as court organist, concertmaster and trusted cammer musicus (chamber musician).

New job, new inspirations

His life and work changed considerably when he gained prestigious employment as Capellmeister (being in charge of music) in the court of Leopold, prince and ruler of Anhalt-Cöthen in what is now Germany.

Leopold and his principality followed the Calvinist faith, a fact that had a major influence on Johann Sebastian’s life. The Calvinist liturgy allowed little if any instrumental music to be performed in the churches of the town, and for six years, between 1717 and 1723, Bach composed mostly instrumental (but not organ) and secular compositions. Bach’s six Brandenburg Concertos, the four Orchestral Suites and inexhaustible supplies of keyboard music, such as the first volume of his famous Well-Tempered Clavier, are all products of these fruitful years.

He also became interested in a genre that was not only new to him but also had little past history that he could rely on, and composed two sets of pieces for solo string instruments: one for violin and the other for cello.

The boldness of this project is hard to appreciate from our 21st-century perspective, but is nonetheless remarkable. By composing for a single string instrument, Bach entered practically uncharted waters.

While there was some existing repertoire written for solo violin, hardly any composer had the temerity to write solo works for a bass instrument, such as the cello. Until the first decades of the 18th century, the cello was seen as an accompanying instrument, providing harmonic foundation and accompaniment to the melody along with a number of other instruments. This was an important and functional role, but without any of the implied glory, virtuosity or elegance of a well-written work for recorder or violin.

A few inquisitive Italian composers experimented with promoting the cello in a soloistic role, but even the best-known of these pieces, Domenico Gabrielli’s solo Ricercari, sounded quirky and innovative, rather than memorably beautiful.

We do not know if Bach was familiar with any of these works. When he decided to compose for solo cello, he chose a different path and turned towards a well-known if by then somewhat old-fashioned genre, the suite. This term refers to a series of dance movements in the same or related keys.

The structure of the suite

Each of Bach’s Cello Suites follows a similar structure. They begin – as was common practice – with a prélude, an introductory movement, which served a dual practical purpose of settling both the unstable gut strings of the cello and the all-too-frequently noisy audience. The prélude is usually the longest movement; its character can be whimsical and improvisatory.

Interestingly, there are no tempo markings for any of the movements given by the composer. Therefore, it is up to the performer to choose the suitable pulse for their interpretation. This can lead to significant differences, as demonstrated by the following two outstanding, but very different recordings of the first, G major Suite’s Prélude.

Here first is Anner Bylsma’s refined and stately performance, as a great example of historically informed performance:

And here is the same movement, played almost twice as fast by the flamboyant German cellist, Heinrich Schiff:

The dance movements, coming after the Prélude, always follow the same sequence, originating from different countries: first comes the Allemande from German lands, then the Courante (French), and then the Sarabande (Spanish). The fourth dance is a pair of so-called Gallantries: Minuets, Bourrées or Gavottes vary between the suites. The final dance is an English Gigue.

Although we have no evidence to suggest the actual order in which the suites were composed, all published versions start with the easiest (Suite I in G major) and move to the hardest.

For Suite V in C minor, following the composer’s instructions, the cellist has to tune the top A string down to G, a process referred to as scordatura. The use of this ingenious technique (common in Baroque times, much less so in our days) changes the cello’s sound considerably. Somewhat confusingly, this means that the performer will play exactly what is in the written music, but will hear different notes from what he or she sees.

The instrument needed for Suite VI in D major is, in fact, a different cello altogether: one with five strings instead of the customary four, again significantly changing the sonority of the instrument. While for the performer the extra string can take some time to get used to, it permits new, otherwise impossible chord combinations to be written and performed.

The Belgian cellist, Roel Dieltiens, maximises this opportunity by deliberately omitting all chords at the beginning of his wonderful performance of the Sarabande of Suite VI, but adding them in their full glory upon the written repetition of the section:

The mystery of the Bach Cello Suites

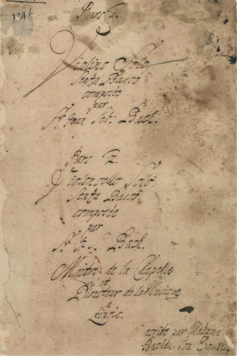

For such a popular set of works, it is amazing how little we know about the genesis of the Cello Suites. Bach’s autograph manuscript of them is lost, with little chance it will ever be found. However, Anna Magdalena Bach, his second wife, copied a large amount of her husband’s works and a copy in her hand of both the Violin and the Cello Solos survives. The two manuscript sets were combined into one volume with the following cover page:

The description is rather long-winded, sprinkled liberally with words in four languages, but it gives the essential information about the two sets, the composer and his copyist wife.

Apart from this manuscript, three other handmade copies survive from the 18th century. While it might be hoped that these copies could help nail down the origin of the suites, they do quite the opposite. All of the four surviving copies contain numerous mistakes and, to increase the confusion, they are vastly different from each other. For these reasons, none of them can be nominated as a truly dependable copy of Bach’s autograph.

This curious circumstance is the main reason for the amazingly large number of published editions of the suites. To date, over 100 musicians (mostly cellists and musicologists) have offered their solution to the problems of divergent notes, rhythms, slurs and other markings between the four manuscript sources. All these editions were prepared with honest musicality and the intent to shine light on obscure details, yet, as a result of the scarcity of reliable sources and the numerous methods to interpret them, they can provide a truly misleading mix of scholarship and speculation.

Although the Cello Suites have not been published for over 100 years after their composition, in our times they are an integral part of the cello repertoire. Most well-known cellists regard performing and recording the whole set as a milestone in their career.

The eminent Spanish cellist, Jean-Guihen Queyras, recently performed the whole cycle (without an interval!) in the Great Hall of the Elbphilharmonie in Hamburg, sharing the stage with five ballet dancers, who presented Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker’s choreography for Bach’s music.

![]() One of the most moving performance comes from the French cellist, Pierre Fournier. His interpretation of the Suites even inspired Ingmar Bergman. The brilliant Swedish film director created a mesmerising wordless scene in his masterpiece Cries and Whispers (1972), in which the terminally ill, exhausted and suffering protagonist, Agnes, feeling abandoned by her sisters, finds solace at the bosom of her maid in a Madonna-like image, accompanied by Fournier’s performance of the Sarabande of Suite V.

One of the most moving performance comes from the French cellist, Pierre Fournier. His interpretation of the Suites even inspired Ingmar Bergman. The brilliant Swedish film director created a mesmerising wordless scene in his masterpiece Cries and Whispers (1972), in which the terminally ill, exhausted and suffering protagonist, Agnes, feeling abandoned by her sisters, finds solace at the bosom of her maid in a Madonna-like image, accompanied by Fournier’s performance of the Sarabande of Suite V.

Zoltan Szabo, Cellist and musicologist, University of Sydney

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

First published: 27 November 2017, 13:15 IST