Breakfast with Mugabe: a play, a friend and a tragedy in two acts

More than a decade ago I wrote a play called Breakfast with Mugabe which was directed by Antony Sher and produced by The Royal Shakespeare Company in 2005. The play suggests why the former Zimbabwean leader spiralled into paranoia – and then remarkably recovered in the build-up to the 2001 presidential elections in Zimbabwe.

The character of Grace Mugabe features strongly in the play, conniving for survival and power during Zanu PF’s last major wobble – to comic, as well as tragic effect.

At the play’s first premiere in Stratford, two suited gentleman showed up – identified by a Zimbabwean member of the company as security police (CIO). They sat in the Swan Theatre, making careful notes. When the play transferred to the Duchess Theatre in the West End, we were visited by a woman claiming to be Grace’s niece and, on another night, by a man who claimed he was a former security guard at State House. Both confirmed details related by the play – including the portrayal of Grace’s bullying temperament.

When the play opened at the Signature Theatre, New York in 2013, a representative from the consulate attended the show after our fearless producer Ezra Barnes spotted that Robert Mugabe was visiting the UN, and extended an invitation. The official maintained an impressive poker face throughout the performance, but his lieutenant for the night could barely keep his shoulders from shaking – giggling helplessly, I’m afraid, at the play’s portrayal of Grace. Afterwards, we were politely, but firmly, informed the president would not be attending.

Our mutual ‘friend’

The second time Grace and I came close, was through my friend, the Zimbabwean journalist and author Heidi Holland, who died in 2012. I’ve been thinking about Heidi a lot as events unfolded this week. Heidi was based in the Johannesburg suburb of Melville where, in addition to her writing work, she kept a guesthouse. I stayed with her in the mid 2000s, on two separate research trips.

Her house was a home-from-home for journalists. At “sundowner” time, the place would miraculously fill with writers from the Johannesburg press pack, plus overseas visitors – many of them passing through on the way up to or down from Zimbabwe. They were often travelling under assumed identities after Mugabe banned foreign journalists from entering the country.

I remember sitting on the end of a bed one night, watching film rushes of the market clearances in Harare. I saw “Bob’s” bulldozers pushing though flimsy shacks, destroying livelihoods with not the slightest care for the life or limb of his own citizens. The policy was called Operation Murambatsvina – “Restore Order” (or, more literally, “Discarding the Rubbish”.

Heidi was a redoubtable journalist. Hearing that I was planning a follow-up play, to focus on Nelson and Winnie Mandela, she immediately unleashed a barrage of phone calls, trying to get me face time with Winnie. When that drew a blank, she insisted on us climbing into her cherry red 4x4 and screeching around Soweto – first trying to doorstep “Ma Winnie” (we passed a copy of Breakfast with Mugabe to the security guards at her house – probably not a productive move) and then staking out a supermarket where, Heidi remembered, Winnie liked to shop. I learned more that day than I really wanted to know about the danger, exhilaration, tenacity and sheer tedium that make up an investigative journalist’s working life.

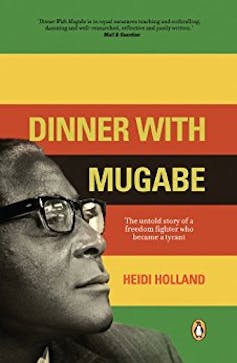

Heidi’s own project at that time was the book she would publish in 2008, the coincidentally-titled Dinner with Mugabe. It tells the story of how, as a young mother with a less-than-liberal husband, she would let the ANC use her house to conduct clandestine meeting with liberation leaders from around Africa – whenever her husband was away on business. Heidi’s role was to make dinner.

One night, the man on the doorstep with his collar turned up and his hat pulled low, turned out to be Robert Mugabe. What follows is a remarkable tale, and confirmed in Heidi the unshakeable conviction that monsters are made, not born – a conviction we shared. Her book also makes clear she was not over-impressed with my analysis of Mugabe’s descent from liberation hero to tyrant.

In the play, Mugabe has been damaged by his imprisonment by white Rhodesia, and driven to the brink by his guilt over the death of Josiah Tongogara, a one-time comrade in the armed struggle and rival for power in the new Zimbabwe.

For Heidi, my portrayal smacked too much of the psychotic-black-African-leader trope – very much a Western way of looking at him. Her own take was subtly different – Mugabe felt deeply slighted on a personal level, and let down politically by the British establishment he so admired. After that, he began to see British imperial strings attached to every opponent, and soon reclassified them all as enemies – to be destroyed, before they could destroy him.

Despite our differences, we joked that once her book was published in the UK, Heidi and I would embark on a joint book tour together, called “Out to Lunch with Mugabe”. Sadly, that never happened, but the book was a great success.

Tragic loss

In 2012, when Heidi’s body was found in her house in Melville, her family confirmed she had taken her own life. It was a great shock to me, as to many. She had her demons, like everyone else, but still … I guess I didn’t know her that well. We were more associates – fellow travellers rather than confidantes, after all.

And then Grace crossed our path again, cropping up in news reports, claiming that Grace had “cursed Heidi” to kill herself. That Grace had waved Heidi’s book at God and asked him to judge if the terrible things in it were true. And now this “white woman” was dead. QED.

If only Grace had known how much she would one day need a journalist like Heidi Holland. Who else in Zimbabwe today is interested in her perspective?

If, during the dark, frightening hours of the coup-that-wasn’t-a-coup Grace had been able to put in a call to the house in Melville, she would have met with absolute professionalism. I can quite imagine Heidi, phone clamped between shoulder and chin, while her hands made a blaze with pen and pad.

Make no mistake, Heidi would have rejoiced in the last few days – she despised everything the Mugabes stood for: the bullying abuses of power, the unabashed kleptomania. But she would have been under no illusions about the incoming president Emmerson Mnangagwa either – and she would have recognised the deep undercurrent of misogyny among those manoeuvring around Robert, blaming everything on the upstart woman. When troops invaded her home and told Grace to “stay in the kitchen” and not involve herself in anything that was taking place, it’s hard not to see a greater significance to those words.

More than that, Heidi would have seen in Grace a fellow Zimbabwean, in deep, possibly irreversible trouble. That is more compassion than Grace has ever showed her compatriots – more, frankly, than she deserves. But Heidi knew what it was like to be in a position of utter defeat, and had a special compassion for the fallen.

![]() I offer the final words of my play in memory of her: “Fambai Zvakanaka”. You’ll travel well, I hope.

I offer the final words of my play in memory of her: “Fambai Zvakanaka”. You’ll travel well, I hope.

Fraser Grace, Fellow of the Royal Literary Fund, Anglia Ruskin University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

First published: 27 November 2017, 19:51 IST