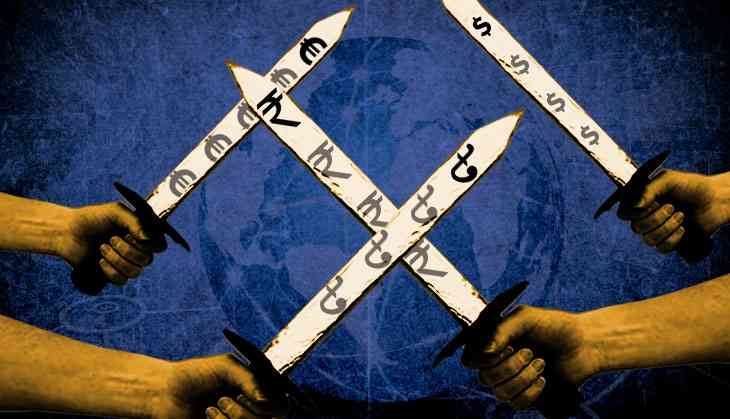

Will Nirmala Sitharaman's romance with a stronger rupee cost Indian economy dear?

India's five-year National Foreign Trade Policy released in April 2015 sets an ambitious target of doubling India's exports to $900 billion (Rs 57.8 lakh crore) by 2019-20 from $466 billion (including services exports) recorded in 2013-14.

The policy aimed at increasing India's share in world exports from 2% to 3.5%. These ambitious targets were announced at a time when India's merchandise exports had been falling for five months in a row and continued the downward journey for 13 months more.

In 2016-17 India’s merchandise exports stood at $274.65 billion, which was a 12% decline from the peak of 2013-14.

World Trade Organization's forecast for world merchandise trade volume pegs 2.4% growth in 2017, but due to a high level of uncertainty, this is placed within a range of 1.8-3.6%.

This uncertainty in global trade comes amid protectionism by developed nations like the United States and European countries and the slow recovery in those economies running on easy-money steroids.

Every country is trying to protect its own exporters to create jobs and push economic growth. It requires multiple strategies that make domestic exporters competitive in the international market. A currency pegged lower in value against the dollar helps exporters of that country become competitive.

But in India's case, a reverse methodology is being appreciated by the Union Ministry of Commerce and Trade.

Since 1 January this year, the Indian rupee has appreciated by 5.94% – making Indian products that much more expensive in the international markets.

On the other hand, the Chinese yuan has depreciated by 0.14%, while the Bangladeshi taka has depreciated by 6.4%, Vietnam’s dong appreciated marginally by 0.11% in the same period.

The Reserve Bank of India's 36 Currency Real Effective Exchange Rate (REER) index, was trading at an all-time high of 118 in March 2017. The index takes in to account exchange rate movements of 36 competing currencies adjusted for inflation differentials.

Exporters have approached the government asking to control the mayhem, but India's union trade minister Nirmala Sitharaman believes that a stronger rupee reflects a stronger economy and there can't be a solution to it.

No two ways about this

In an interview to Mint, Sitharaman said a stronger rupee reflects the strength of the Indian economy and exporters need to live with this new reality. “Unlike China, we have not really put our focus only on exports and export-driven growth,” she further added.

Sitharaman's statement goes against the overarching narrative built by the Modi government over the past two years that India wanted to be the manufacturing powerhouse of the world.

China's exports are six times that of India, and India's eastern neighbour has used competitive currency, for over a decade, to reach this level.

Not all in the government share Sitharaman's view though.

India's Chief Economic Advisor in the finance ministry Arvind Subramanian recently said: “That is a mistake that we should not make and that is something we should be careful about. If you look at the last two years, our country has lost competitiveness from exchange rate by 10-15% and that is a huge loss in competitiveness that is affecting our exports”.

Subramanian added, “If the currency becomes too strong, it is not easy to keep open markets because a lot of goods come in and the industry feels the pressure.”

Subramanian had made a detailed argument in the Economic Survey, released before the budget in February, saying that India's actual growth in the short run will also depend upon global growth and demand.

“After all, India’s exports of manufactured goods and services now constitute about 18% of GDP, up from about 11% a decade ago,” the survey said.

Time and again, Indian finance ministers have talked about achieving an above 8% GDP growth for a decade to make India a developed country. But it is unlikely that it can be achieved without taking a forward leap in the exports.

Exporters feeling the pinch

“Indian engineering exports have become expensive and exporters are finding it tough to get new orders. We have requested the government to support us in some way, as now it is expected that the Indian currency will even appreciate to the level of Rs 60 to a dollar.” said SC Ralhan, former president of Federation of Indian Export Organisations.

"Due to an overvalued currency, India is losing out to smaller countries like Bangladesh and Vietnam. Due to higher labour costs in China, many garment manufacturing orders should come to India, but because the Indian currency is overvalued and the government does not do much to compensate exporters for that, those orders are going to Bangladesh and Vietnam,” DK Nair, a foreign trade expert, said.

While Bangladesh's garment industry made exports worth $28.09 billion in the fiscal year 2015-16 with a 10.21% growth from the previous year, Vietnam's registered fabric and garment exports are worth $23 billion in 2016. India's garment experts were at just about $17 billion in the same period.

Is there a reason for allowing the appreciation of currency?

Deepak Nayyar, emeritus professor of economics, Jawaharlal Nehru University, in an article published in Mint newspaper in January 2016, had explained the reason behind India's fetish with an overvalued currency.

“It might just be a camouflage for the real reason, which is never made explicit. This stems from the compulsion of financing large current account deficits (in the balance of payments) through capital inflows provided by foreign institutional investors. The economy needs a strong exchange rate for confidence, together with high-interest rates for profitability, to sustain such portfolio investment.”

“This solution often turns out to be worse than the problem. It erodes the competitiveness of exports over time and enlarges the trade deficit. Larger trade deficits and current account deficits require larger portfolio investment inflows, which beyond a point undermine confidence, and create adverse expectations, even if the government keeps the exchange rate pegged.” said Nayyar in his article.

Shankar Acharya, a noted economist and former chief economic advisor to the government of India in an article published in Business Standard on May 2017 said, “The history of global economic development since 1950 does not support the view that long periods of a strong currency have been good for growth and development of nations.”

On the contrary, Acharya further adds, “The best practitioners of sustained rapid growth, mostly East Asian economies such as Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, China and Thailand, generally eschewed currency strength and opted to maintain competitive exchange rates to help gain market share in global trade.”

A lesson from Brazil

Between 2009 and 2010, the Brazilian 'real' appreciated 40% against the dollar. Before 2009, Brazil had a $15 billion trade surplus with the US, which turned to $6 billion deficit due to the sharp appreciation of the currency. A stronger real made imports cheaper allowing US companies to dump their products in the South American nation.

Unhappy with the situation, Brazil's finance minister Guido Mantega, on 27 September 2010, said, "We are in the midst of an international currency war."

The job problem

Every month, one million (10 lakhs) new people enter the job market in India. Over the past three years, job creation has not crossed five lakhs a year. A large reason for this is the shutting down of exporting units in the country, especially in the textiles, gems and jewellery and leather industry.

In the coming years, the problem will only aggravate as the high-end jobs in the Information Technology sector too have begun to shrink due to changes introduced in the H1B visa policies of the US- India's largest IT export market – forcing companies to hire locally instead of employing Indian engineers.

This puts additional pressure on Prime minister Narendra Modi who desperately wants to prove that his government's economic polices will deliver sustainable growth to the country.

This is why, the sooner Sitharaman understands the link between exchange rates, exports, economic growth and job creation, the better it will be. If any doubt persists, she should remember what US treasury secretary John Connally said to foreign finance ministers in 1971:

"The dollar is our currency, but it is your problem."

First published: 12 May 2017, 14:26 IST