Harvey Weinstein: showbusiness voices signal the sad ubiquity of sexual abuse in industry

When sexual harassment happens it’s shocking and terrifying, but it’s like a bad dream you have always been braced for. At least that’s what it felt like when it happened to me as a young woman trying to establish a career as an actor.

I proudly got my Equity card in 1989, the same year that Michael Rubenstein, wrote:

Sexual harassment is a new term for an old phenomenon. For generations of women, unwanted sexual attention has been an inescapable part of working life. Yet, until recently, this behaviour had no name. Without a name, it was not recognised as a problem suitable for discussion. As it was not seen as a problem, there were no solutions. Once sexual harassment was given a name, it rapidly became clear that the problem was commonplace.

My own experience, and the Harvey Weinstein allegations, are nothing to do with showbusiness per se. Sexual harassment and sexual assault are part of many women’s working lives and have been since at least the Industrial Revolution. But when the work is project-based there is more opportunity for illegal (at worst) or boorish (at best) behaviour.

Oversupply

In an industry structured around hundreds of different types of project, individuals often operate without organisational scrutiny. Recruitment and selection can legitimately take place in a range of environments, including private houses and hotel rooms. Here, individual workers are just that – individuals in a chronically oversupplied, geographically dispersed industry that operates on short-term contracts with different employers.

As one performer who has been working in theatre, television and film since the 1980s said in my research on actors as workers:

The bottom line for everyone is: ‘Will this bastard employ me again?’… It’s a brutal mix – you’re like a lovesick teenager waiting for the phone to ring, you’re a professional and you’re poor. And employers know it and know that there are plenty more where you came from.

This was echoed by a former senior executive at one of Britain’s leading theatres:

There are still plenty of employers of performers who are unscrupulous, to a degree. Who know that they can be, because for every one they employ there are five who are waiting to take the job. Fifty, in some cases. So it’s still a very, very vulnerable and potentially corrupt and exploiting sector, because of that very thing.

One current entertainment industry union official made a related point:

Our members won’t go public – you get lots of stories with members phoning up but then saying they won’t make a fuss … If someone gets a bad reputation in this business they don’t work again.

Another union official said:

It’s much more about before you get the job. You have to impress so many people all the time. Can’t do it once. You have to do it all the time.

This pattern of trying to build a career where no career path exists offers opportunities for abusive behaviour. The endless supply of actors means that it is a genuine risk to a career to report behaviour of the kind Weinstein is accused of displaying.

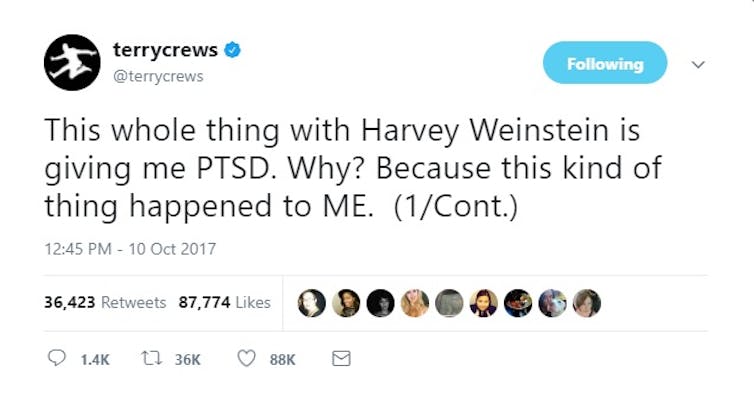

Acting is also a vocational job: actors of all genders have a drive to do this particular work, where competition for a small number of jobs is usually segmented into even smaller categories by age and physical type. This usually means that actors often work for low or even no pay. For women (mainly though not exclusively – see Terry Quinn’s revelation of abuse there is the added dimension of sexualisation.

Cast in stone

In my research, gatekeepers to employment such as casting directors acknowledged that male directors and producers often made irrelevantly sexualised recruitment demands: as a woman television producer put it, “casting fantasies”.

One casting director was clear that the selection of performers regularly involved inappropriately personal judgements:

You have to be quite careful. And I often say [to directors] I am not here for the delectation of your loins actually.

This was echoed in my US research where one writer talked about being in a television movie casting meeting where the producer turned down the first choice of actress because: “I don’t want to fuck her.” This was presented as a serious selection criterion. Anti-discrimination legislation does not reach into such meetings.

Again, this is associated with the entertainment industry, but it is dangerous to focus too narrowly here, for the conditions in showbusiness are only the most fertile for exploiting an imbalance of power that exists in all employment. Many academics have argued that women are regarded as “woman” (and thus, bodies) first and “worker” second and that this affects employment more widely.

This is about a continuum of attitudes and behaviour. A 2016 report on workplace sexual harassment by union body the TUC made that clear. The Weinstein story is about one end of that continuum.

![]() What is remarkable about this miserably ordinary story is that it makes the workings of power visible. This is the value of it being a showbusiness story with famous people involved. If naming sexual harassment meant we could identify it as a problem, then talking publicly about it – through the stories of the brave actors who are speaking out – means something else. It means we are closer to redefining what is expected and acceptable in the exercise of power in the workplace.

What is remarkable about this miserably ordinary story is that it makes the workings of power visible. This is the value of it being a showbusiness story with famous people involved. If naming sexual harassment meant we could identify it as a problem, then talking publicly about it – through the stories of the brave actors who are speaking out – means something else. It means we are closer to redefining what is expected and acceptable in the exercise of power in the workplace.

Deborah Dean, Associate Professor of Industrial Relations, Warwick Business School, University of Warwick

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

First published: 14 October 2017, 18:39 IST