Why Pak is so flustered by Husain Haqqani's recent Washington Post article

An article in The Washington Post on 10 March by former Pak ambassador to the US, Husain Haqqani, has set the cat among the pigeons in Pakistan.

Haqqani’s article has to be seen at three levels:

First is at the domestic level in the United States, where he basically said that there was nothing inherently wrong in the Russian ambassador meeting people from US President Donald Trump’s team before the election.

Haqqani quoted his own example in 2008 when the US State Department facilitated the participation of Washington-based ambassadors in the Democratic and Republican national conventions that year “where the more active and better-connected ambassadors, including myself, were able to meet personally with people we expected to have major roles in the conduct of foreign policy after the election. There was nothing unusual, let alone treasonable, in this”.

Business as usual

In other words, the article defends the Trump team, which has contacts with the Russian ambassador to the US, calling it business as usual and unworthy of the scrutiny and criticism that it is currently on the wrong end of.

At the Pak-US bilateral level, Haqqani says he saw and advanced the mutuality of Pak-US interests.

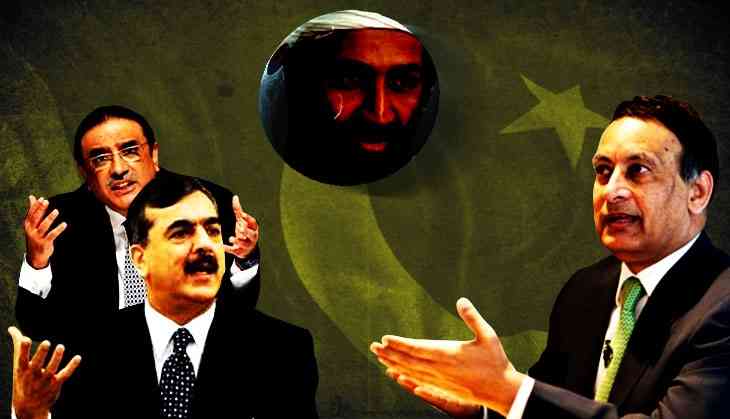

These interests, as made clear to him by the civilian government of former President Asif Ali Zardari and Prime Minister Yousuf Raza Gilani was to end Pakistan’s support for the Taliban, improve relations with India and Afghanistan, and limit the role of Pakistan’s military intelligence service in defining the country’s foreign policy.

In return, they sought generous US aid to improve the ailing Pakistani economy.

Common interests

US interest, as articulated by Barack Obama in a major speech in 2008, when he stood foe election, was to make “the fight against al-Qaeda and the Taliban the top priority.”

Haqqani leveraged this commonality of interests and noted that after Obama took office, this is exactly what happened: civilian aid to Pakistan was enhanced to record levels in an effort to secure greater cooperation in defeating the Taliban. The Kerry-Lugar-Berman Act of 2009 authorised the release of $1.5 billion per year to Pakistan as non-military aid from 2010 to 2014.

The third level is in Pakistan’s domestic context where he says that a spin-off from the relationships he forged with members of Obama’s campaign team was when they requested the stationing of US Special Operations and intelligence personnel on the ground in Pakistan. These requests were brought directly to the attention of Pakistan’s civilian leaders, who approved.

“These connections eventually enabled the United States to discover and eliminate bin Laden without depending on Pakistan’s intelligence service or military, which were suspected of sympathy toward Islamist militants,” Haqqani writes.

The timing

Similar revelations about the issue of visas had appeared at the time of the Memogate enquiry.

What is new is Haqqani’s emphasis that these locally stationed Americans to whom visas had been issued proved invaluable when Obama decided to send in Navy SEAL Team 6 without notifying Pakistan.

What has caused a flutter is its timing.

For one, it comes immediately after the publication of a report by the Hudson Institute titled ‘A New U.S. Approach to Pakistan: Enforcing Aid Conditions without Cutting Ties’ and co-authored by Husain Haqqani and Lisa Curtis of the Heritage Foundation.

The report argues: ‘The objective of the Trump administration’s policy toward Pakistan must be to make it more and more costly for Pakistani leaders to employ a strategy of supporting terrorist proxies to achieve regional strategic goals. There should be no ambiguity that the US considers Pakistan’s strategy of supporting terrorist proxies to achieve regional strategic advantage as a threat to US interests.”

What Haqqani’s article has done is reinforce this report by rekindling memories of Osama bin Laden hiding in Pakistan and the US taking him out without the knowledge of the military establishment due to lack of trust.

Secondly, it has brought into sharp focus the fact that the report of the Abbottabad Commission has still not been made public.

The Pakistani public and the world at large still don’t know how Osama bin Laden reached Abbottabad. More importantly, how did he and his family live there for so many years without being detected?

Moreover, there is the overarching question: whether it was the complicity of the Pakistan security establishment that allowed a US ground operation inside Pakistan or the abject failure of that much-vaunted system to detect and deter such an intrusion.

The political angle

Thirdly, at the receiving end of Haqqani’s disclosures is the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP), especially former president Zardari and former PM Gillani. They will be hard pressed to explain why and how they authorised Haqqani to issue visas to a large number of CIA operatives in Pakistan, bypassing vetting by the military establishment.

That the party is fumbling for a coherent strategy is obvious from the contradictory remarks that have come the PPP leaders, varying from calling Haqqani a traitor, to his being under pressure, to “no procedures were violated”.

Well before the article was published, the PPP was trying to distance itself from Haqqani, possibly in an effort to patch-up with the ‘Establishment’ in the run-up to the 2018 elections.

If so, the strategy has boomeranged. The Establishment would be enraged about the bin Laden affair being re-kindled at a time when the new US administration would be formulating a Pakistan policy while Haqqani himself may have been infuriated for being made the sacrificial lamb.

While the PPP fumbles, Haqqani is sticking to his guns. In an email to Dawn, he said on 12 March that he had “retained complete record of every visa issued to US officials” while he served as ambassador and that he would be compelled to make the authorisations public, “if conspiracy theories continue to be circulated to target the patriotism of civilians.”

The controversy over the article would come as much relief to Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif since it has, at least temporarily, diverted attention from the impending verdict of the Supreme Court in the Panama Papers case.

This is clearly not the end of the story. With some in Pakistan calling for a Parliamentary or Judicial Commission to enquire into the whole issue, the last word has not been spoken on the matter.

Edited by Aleesha Matharu

First published: 17 March 2017, 19:46 IST