How neo-nationalism went global

For more than ten years, the world has been witnessing a sharp spike in nationalist tensions, coupled with flare-ups in xenophobia and nativism. ![]()

But it took Brexit and the election of Donald Trump to spark a real conversation about the global rise in neo-nationalism. Western European and North American journalists, intellectuals, and academics are just now getting to grips with the magnitude of this trend.

This is no doubt understandable, given the concrete prospect of profound political change taking place within the world’s leading power, and upcoming elections in founding EU countries. Donald Trump, Nigel Farage, Marine Le Pen and Geert Wilders remain the most commonly cited figures in this new nationalist landscape.

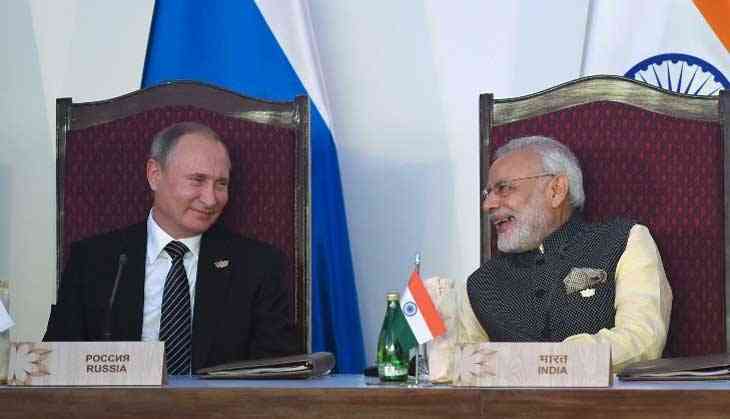

Hungary’s Viktor Orbán, Poland’s Andrzej Duda and Turkey’s Recep Tayyip Erdoğan often come in for a mention, as do India’s Narendra Modi and the Philippines’ Rodrigo Duterte. But we are yet to draw up a complete family tree of neo-nationalism worldwide.

The West: anxious, yet somewhat removed

Twenty years ago, commentator Fareed Zakaria denounced the rise of “illiberal democracy”. In South America, North Africa, the Middle East, the Balkans, South and South-East Asia, democratic elections – sometimes overseen by international observers – had given rise to authoritarian, ultra-nationalist regimes, quick to eviscerate the civil liberties and rights of opponents to their nationalist program.

However, putting aside the Balkan States, the phenomenon did not appear to directly affect Western countries. In the heart of Europe, the fall of the Berlin Wall had given rise to a powerful geopolitical narrative – one that proved lasting, despite early signs of structural weakness.

It told of the destruction of all walls across the globe, and of a joyful and irresistible melding of societies, benefiting the new transnational powers. In this view, favoured by international companies and supported by international NGOs, economic liberalisation would go hand in hand with political liberalisation.

Under the influence of this optimistic outlook, Western public debate saw “illiberal democracy” as a side concern. However, over the years, what was supposed to be peripheral and secondary became surprisingly substantial and overcame the mental barriers meant to contain it.

The future of the global far-right

The August 2010 visit by a delegation of far-right European parliamentarians to the Yasukuni shrine, a Mecca for Japanese historical revisionists, was a sign of the coming “globalised nationalism”. While the meaning behind this Japanese-European meeting (a shared disdain for remembrance) was reported by the few media outlets that covered it, this fact in itself did not appear to point to a worldwide political trend.

In hindsight, it was telling in more than one way. It was a display not of the past but of the future of the global far-right, and it demonstrated new, improbable, yet highly effective transnational ties between nativists.

With the new generation, the far-right has certainly undergone a makeover, but its core principles remain.

What has really changed is our level of tolerance for a kind of discourse that was barely admissible, let alone heeded, a few years ago. The tiny organisation Issuikai, which played host to the European MPs at the Yasukuni shrine, espouses a rampant nationalism that was clearly relegated to the outskirts of the Japanese political landscape at the time.

Today, the movement is represented within Shinzô Abe’s government, notably by Defense Minister Tomomi Inada.

Similarly in Russia, as Charles Clover notes, pan-Russian hyper-nationalism, still on the far fringes of politics at the beginning of the millennium, has found its way to the Kremlin, and now shapes Vladimir Putin’s official discourse.

From the fall of the Berlin Wall to Trump’s Wall

The creation of the BRICS forum, bringing together Brazil, Russia, India, China and later South Africa was initially seen as the assertion of a new non-Western, or even post-Western power. However, its real combining force was a militant nationalism, ill at ease with global governing bodies that were perceived as too intrusive.

This is even more evident today, with the nationalist escalation taking place in Moscow, Bejing, New Delhi and, to a lesser extent, in Brazil, where ultra-nationalist Jair Bolsonaro is fast gaining ground. The alliance between neo-nationalist leaders now cuts through the Western/non-Western divide, as demonstrated by Vladimir Putin’s support for Donald Trump and Marine Le Pen.

Collusion between new nationalists may seem improbable and even antithetical, given that nationalist dogma is, by nature, separatist. Yet it has enabled the development of a remarkably powerful worldwide narrative, in direct opposition to the optimistic globalisation of the post-Cold-War period.

In the 1980s, Ronald Reagan demanded that Mikhail Gorbachev destroy the Berlin Wall. Thirty years later, Donald Trump proclaims that the world needs more walls between nations. This new vision of a world crisscrossed with walls is easily propagated with the help of globalisation’s ultimate tools: the internet and social media.

Hi-tech populism

Without access to mainstream media outlets, those whose neo-nationalist convictions were decidedly on the fringe ten years ago focused their energies on the manifold possibilities for communication, rallying and sharing provided by the internet.

In tune with their supporters, the major figures of nationalist populism are also masters of “hi-tech populism”, as commentator Aditya Chakrabortty described Narendra Modi’s modus operandi. Before being overtaken by Donald Trump, the Indian Prime Minister held the record for the highest number of political tweets. Traditional politicians are simply not as well connected as the new nationalists.

Invited to the Conservative Political Action Conference in Washington, the leader of the pro-Brexit campaign, Nigel Farage, called for a “global revolution” led by nationalists of all countries. Meanwhile, the few remaining advocates for an open, interdependent world appear to show no interest in organising a cross-border movement on such a scale.

Translated from the French by Alice Heathwood for Fast for Word.

Karoline Postel-Vinay, Directrice de recherche, Sciences Po – USPC

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

First published: 16 March 2017, 15:20 IST