Why Modi's Smart Cities project hasn't proven to be all that smart after all

The Narendra Modi government keeps on trumpeting about its ambitious programme of developing 100 smart cities. But is the “Smart Cities Mission” really a classic case of much ado about nothing? Well going by the fact that only 8% of India’s total population is likely to benefit, it seemingly appears to be so.

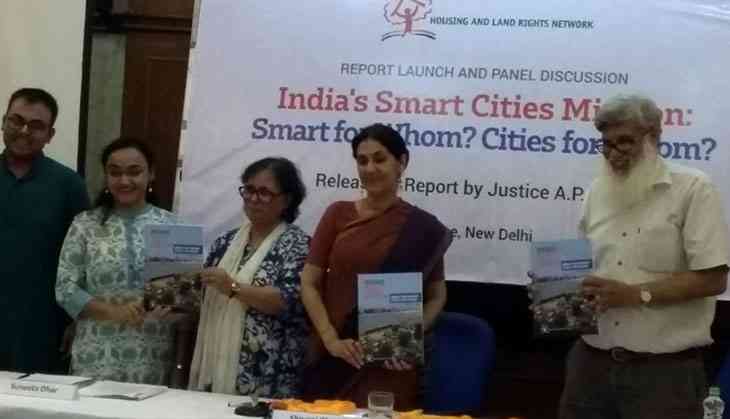

Advocacy group Housing and Land Rights Network (HLRN) on Friday released a report detailing the many shortcomings of the ambitious project announced by the Prime Minister in 2015, entailing a total proposed investment of over Rs 2 lakh crore.

Exclusionary approach

The reports titled "Smart from Whom? Cities From Whom?" states, that by focusing on only 100 cities and on select areas within those cities, the Mission demonstrates a restrictive approach to urban development. It points out that 80 % of the total proposed investment of Rs 2.04 lakh will be spent on ‘Area-based Development’ (ABD) or only on specific areas in each city, with only 20 per cent of funds being devoted to ‘pan-city development’.

“The city area covered by ABD is less than 5 per cent for 49 of the 86 cities for which information is available. The government claims that 99.5 million people or only 8% of the total population or 22 per cent of the urban population will be covered by Mission projects,” says the report.

Rising trend of the privatisation of governance

The Mission Guidelines require each ‘smart city’ to create an entity called the special purpose vehicle (SPV) to be established as a limited company incorporated under the Companies Act 2013, in which the state and urban local body have 50:50 equity shareholding.

This measure has been criticised as a direct violation of the Constitution (Seventy-fourth Amendment) Act 1992, which divests power in local governments and urban local bodies. The competing governance mechanism created by the SPV, while resulting in overlapping powers, could substantively dilute local democracy, states the report.

The report also raises questions on increased corporatisation of cities.

It is estimated that the implementation of India’s Smart Cities Mission would require investments worth 150 billion US dollars over the next few years, of which 120 billion dollars would be required from the private sector.

The selected cities are, thus, raising funds through a variety of Public Private Partnership (PPP) models with large companies, including several big multinational players, likely to be the greatest beneficiaries.

As of May 2018, PPP projects worth Rs 734 crore had been completed in 13 cities while projects worth Rs 7,753 crore were under the implementation/tendering stage in 52 cities. These trends highlight the subtle and irrevocable transition towards the corporatisation of Indian cities, with grave potential implications for governance as well as the fundamental rights of residents, the report said citing government figures.

Dependence on foreign investment

With a host of foreign governments and international agencies funding, either for general support to the Mission or for specific city-projects, the report states that there exists a “concern about the level of control” that local governments will have over decisions and outcomes related to ‘smart city’ projects.

Failure to address rural-urban linkages

As per the report, the Mission has adopted a rather limited approach and reinforces the erroneous policy assumption that ‘urbanisation is inevitable,’ thereby ignoring the need to take concerted measures to address distress or forced migration to urban areas by investing in the needs of rural people, responding to acute land and agrarian crises, and developing rural areas with adequate budgets and investment plans.

Absence of human rights-based standards and monitoring indicators

With the absence of any human rights-based indicators to monitor implementation, the report raises question on the Mission’s ability to deliver on its aims and ensure the fulfilment of rights and entitlements of all city residents. It points out to the lack of a city development model and adequate standards to guide project implementation, including for housing, water, sanitation, health, and environmental sustainability.

Non-recognition of housing as a human right

While the Mission raises the issue of housing for economically weaker sections (EWS) / low-income groups (LIGs) in their proposals, none of the cities have recognized housing as a human right or included standards of ‘adequate housing,’ especially those related to appropriate location, affordability, and tenure security.

The report also raises concerns on the threat of forced evictions, land acquisition, and displacement.

Smart enclaves

Describing the project more as developing “smart enclaves” than “smart cities”, the report states that the Mission will lead the costs of real estate—including commercial rental rates and housing prices in the area—to rise, fueling the threat of market-led evictions and gentrification of ‘smart’ neighbourhoods.

Besides the risks of digitisation and threats to privacy the report also raised environmental concerns.

Recommendations

An analysis of the Smart Cities Mission reveals the glaring absence of a human rights-based approach as well as a neglect of the urban poor and marginalised, the HLRN has made several recommendations to ensure a greater focus on human rights, equality, and social justice.

First and foremost it has recommended a human rights-based implementation and monitoring framework to assess the achievement of targets and to ensure that all ‘smart city’ projects comply with national and international law and promote human rights and environmental sustainability.

It also calls for developing a special focus on the needs, concerns, and human rights of marginalised individuals, groups, and communities, including children, women, Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes, migrants, homeless persons, domestic workers, persons with disabilities, religious and sexual minorities, and other excluded groups.

It also recommends strict measures to ensure that implementation of ‘smart city’ projects does not result in the violation of any human rights, including the rights to adequate housing, work/livelihood, security of the person and home, water, sanitation, health, food, privacy, information, must be protected.