Solidarity with anti-Padmavati protestors makes RSS see entire Bollywood as anti-Hindu

If you are a Hindi film enthusiast, can you recall your favourite negative characters till just before the 1990s? Gabbar Singh, Mogambo, Shakaal, Lion, Teja, Robert, Prem Chopra, Ranjeet, Gajendra, Sukhi Lala are only some of the names that flash in a jiffy. Do you remember their religion? Or caste? Or specifically any feature that would indicate a systematic portrayal of the villain as Hindu and the do-gooder as Muslim?

The Sangh Parivar likes to believe this. According to Balmukund Pandey, an RSS pracharak and national organising secretary of the Sangh’s history wing, India's Hindi cinema has an anti-Hindu bias and that Hindus were shown as villains in the movies before 1990.

“When there is an evil person, he would be a Thakur or Trivedi, who will be the girl’s father troubling the boy. If it’s someone dishonest, he’ll be a businessman, if there is someone who’s a fraud or impostor, he will be Brahmin who wears teeka on his forehead…. And wherever there is a character, it will be some Rahim bhai aur Fahim bhai,” Pandey said on 29 November at the Daulat Ram College in Delhi University.

He was speaking against the background of the mind-boggling controversy over film-maker Sanjay Leela Bhansali's yet-to-be-released film, Padmavati. The hyper-ventilating Karni Sena and the ilk have already had their knickers in a twist over the movie. As of they had not unleashed enough lunacy already, the RSS appears to have decided to amplify their campaign.

Historians' negation of Padmavati as an actual historical character be damned, Pandey believes she was “our mother”. To him, why her name can not be found in historical texts is because Alauddin Khilji destroyed all the libraries in Rajasthan.

It was while attempting this impossible defense of the indefensible that Pandey exposed another example of how RSS invents enemies where there are none. Accusing entire Indian Hindi cinema of being anti-Hindu is as senseless as it is devoid of evidence.

In the first wave of Hindi cinema after Independence, most films were based on social themes and the stories depicted lives of the masses in urban as well as rural India.

There was hardly a villain in many of the early movies. Tragedy was inflicted upon the lives of the protagonists directly or indirectly by the socio-economic order. No particular character was held responsible.

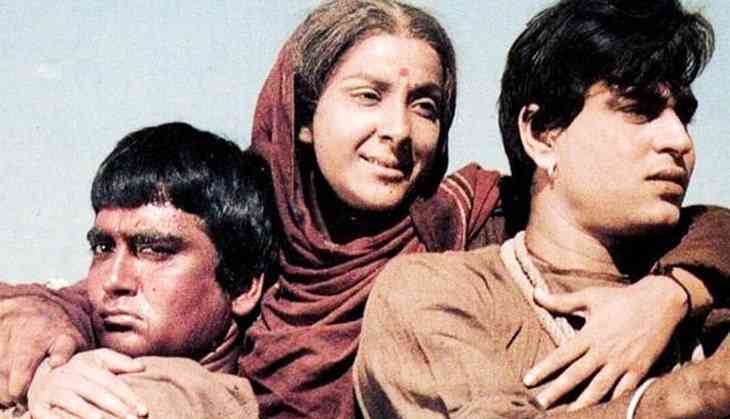

In some other movies, this exploitative reality was personified in one character, who was either a feudal lord (Harnam Singh of Do Beegha Zameen, Ugra Narayan of Madhumati), or a moneylender (Sukhi Lala of Mother India, Dhaniram of Kanoon). Such portrayals mirrored the reality of that era, with the society gripped in the trappings of a feudal social order and yet striving to move out. A conscious depiction of a negative Hindu character or a heroic Muslim was non-existent.

Caste could still be felt with the villains' surnames and backgrounds, but communal angles were virtually left untouched.

Then there were the love stories that barely touched upon any social tensions.

The 1970s and the 1980s were largely the age of the Amitabh Bachchan's 'angry young man' character, wronged most often by a criminal don (Teja of Zanjeer, Samant of Deewar) or a corrupt businessman (Zafar Khan of Coolie).

There was hardly any attempt to pit a Hindu villain against a Muslim hero in these films too. So while Sholay's bandit Gabbar Singh could have been an upper caste Hindu, Jai and Veeru were not depicted as Muslims. Zanjeer's Teja and Kaalicharan's 'Lion' could have belonged to any religion, but Vijay and Kaalicharan weren't meant to be Muslims at all.

The religious identity of Shaan's Shaakal is not clear but Vijay and Ravi are certainly not Muslim. Similar is the case with Bobby's Prem Chopra. The villain Robert in Amar Akbar Anthony's, however, was certainly Christian, not Hindu. One can be mistaken for assuming Mr India's Mogambo too as Christian, while there can hardly be any ambiguity about the religious identity of the hero, Arun Verma.

The kind of cinema that took root in 1990 and which Pandey has beeen kind enough to exempt from his assessment had begun with some hits of the 1980s. While Chandni (1989) had no particular villain, Qayamat Se Qayamat Tak's villains were two Hindu upper-caste feudal families (1988). Even the negative characters in Maine Pyar Kiya (1989) were scheming Hindu friends/relatives of the hero's rich, Hindu upper caste family. No Muslims anywhere.

Pandey's accusation is the product of a conspiratorial mind that the Sangh Parivar's views represent. It can be laughed at and brushed away, but for the fact that this fraternity is in power today. One can only hope in these times that the government of the day too turns a deaf ear to such insane laments.