Nine photographers 'Witness' 30 years of troubled Kashmir in one book

_55302_730x419-m.jpg)

When it comes to pictures, Kashmir’s defining image has always been a shikara anchored on the shimmering, uncluttered expanse of the Dal lake against the backdrop of Zabarwan Hills or the Hari Parbat.

Google Kashmir and Dal, shikara, Zabarwan Hills, Hari Parbhat shows up in by and large undifferentiated compositions among a melange of images.

But this is not an accidental or a default image. It has earned its place over decades of painstaking work by an institutional machinery geared to project, and protect, Kashmir in 'touristy' terms. The image has a salutary utilitarian objective – to draw more holidaymakers to the place.

It is a project aided in part by Bollywood – right from Raj Kapoor’s Barsaat to Salman Khan’s Bajrangi Bhaijan – and in part by other institutions. And along the way, Dal and its heavenly surroundings have not only monopolised the pictorial and video representations of Kashmir, but it has also largely dictated how the world generally looks at the state. Like this video:

True, other allied images have also played a role in portraying Kashmir as a touristy paradise. For example, the Dal and shikara emblems soon came to be accompanied by a shot of snow peaks of Gulmarg, fresh water streams of Pahalgam or meadows of Yusmarg. Nature in all its splendour – but sans people.

Was this exception deliberate? The answer hardly matters.

It may as well have been an unwitting exception, but it is an exception made witting by what it confirmed – the absence of an institutional consciousness about the people.

An exception that presupposes people as extraneous to the commercial project of attracting tourists to the state. One that assumes that the juxtaposition of the pictures of the people and the glorious untouched nature somehow undermines the beauty.

And one can very well see why. The gorgeous nature stays silent and disguises the reality, but the faces of people, once captured in their authentic surroundings, won’t.

The thing about exceptions...

But that this exception may not be deliberate hardly detracts from the politics of it. It only goes on to prove that the obliviousness to the people is inbuilt into the system and that there is no inherent recognition of their existence and inextricability to the purpose of the larger public good.

Or to put it in less complex terms, the institutional understanding of what is good for the place doesn’t actually encompass the people, informed as it is by a narrow touristy focus which believes exclusively in the pull of nature and its obfuscating and obscuring potential.

So what must they obfuscate? The lives of the ordinary people there.

It may appear unbelievable that a signature image and its variants reinforced by Bollywood song sequences could so colonise the public conception of a place so torn apart by conflict and tragedy. Designed to sustain Brand Kashmir and its conceptualisation as the paradise on earth, these images imperceptibly serve the function of evacuating the state of the mess of its lingering turmoil.

A reminder about that is in order here:

– More than 70,000 people have lost their lives over the past three decades

– Around 8,000 are missing

– Several hundreds have been blinded and thousands maimed.

And a deeply scarred population is mopping up the unfolding humanitarian fallout.

So formidable has been the officially-propped up paradisiacal idea of Kashmir that even 30 years of an alternate photographic history and its constant play in the media has struggled to displace it.

The Dal and the shikara continue to invariably compete for visual attention to reassert the fantasy, or at least, temper the bitter taste of the reality as any random Google search will testify. Or set aside Google check, the touristy images lurk so deep in the world’s mental picture of Kashmir that even a summer of hundred killings and mass blindings cannot cast these away.

Witness me

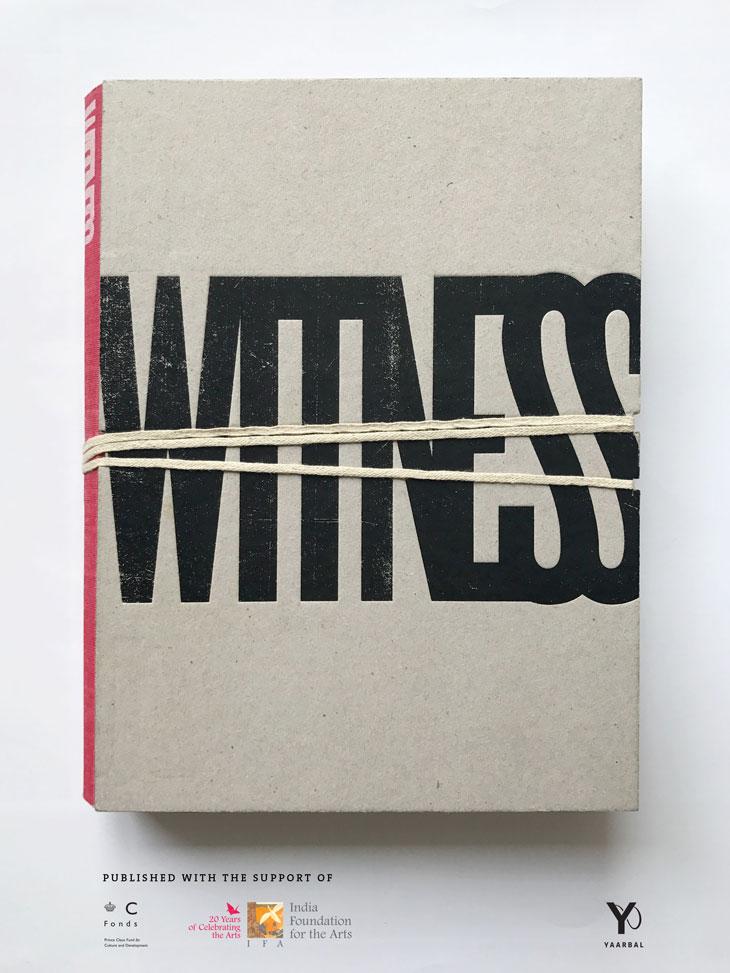

This is where Witness, a new book of photographs on Kashmir, finds its place and a vital role. Witness' editor Sanjay Kak states its purpose clearly and bluntly at the beginning – “For those who live in Kashmir's present and are witness to its troubles, the endless celebration of its fabled beauty has turned many of these charms leaden. Few have delighted more in their landscape than those who colonised it,” writes Kak as he recalls Emperor Jahangir's exclamation on seeing Kashmir – “If there is a paradise on earth, it is here, it is here, it is here.

“Five hundred years later that imperial delight continues to work the way into our present, transformed into an advertising hook, giddy words aimed at drawing in tourists.”

The book publishes the works of nine photographers – Mehraj-u-Din, Javeed Shah, Dar Yaseen, Javed Dar, Showkat Nanda, Altaf Qadiri, Syed Shahriyar, Sumit Dayal and Azan Shah – and covers the period from 1986 to 2016.

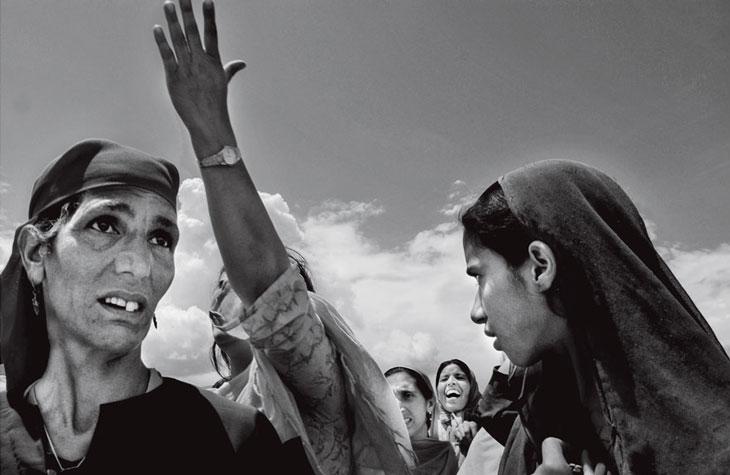

Together they confront the state's narrative with its biggest challenge. The pictures unveil a Kashmir beyond the Dal and the shikara, the other side of Zabarwan and Hari Parbat.

They take the viewer into the lanes and bylanes of Srinagar and further into the countryside, its mofussil villages, orchards and fields, into the homes and kitchens of the people.

These pictures are not about the geography of Kashmir, but its inhabitants. They are not about the faces, but their stories. Not about the dumb timelessness of nature, but the witnessed panorama of events and incidents that have shaped its history. They are about the truth, its many shades and contestations.

And this is how the hitherto obfuscated people emerge from behind the shadow screens.

The Witness brings you frame-by-frame the troubled three-decade-long story of Kashmir and puts it in the front and the dead centre. And as Kak tellingly describes it, the book “plants a flag in the contested land” and asserts the intrinsic truth of the people in the teeth of the fantasy spinning official discourse.

Framed it

The very first picture snaps you out of the induced forgetfulness – the body of the sessions judge Neel Kanth Ganjoo sprawled right in the middle of busy thoroughfare at Lal Chowk.

The picture clicked by Mehraj-u-Din, seconds after the assassination, sets the stage for the blood-soaked play of the competing nationhoods, ideologies and the aspirations that have unfolded since.

The aspects of this unremitting play come back to life in the frames of the nine photographers led by the senior-most of them all – Mehraj-u-Din – MD for the journalistic fraternity and his many admirers.

His pictures, which are a witness to the beginnings of the armed conflict, are followed by those of Javeed Shah.

Shah’s frames go beyond the immediacy of the moment being photographed and lingers on to capture its larger historical significance, with a deeper intellectual meaning and an artistic distinction to boot.

His picture taken immediately following a fidayeen attack in Srinagar defines the conflict over the state – a blur of blood drawn across asphalt under a Kalashnikov dangling from the hand of a passing cop.

The young Javed Dar ushers in the movement, energy and drama. “Welcome to Gaza” reads a graffiti scrawled across the side of a flyover as the underpass beneath it reveals the forces in riot-control gear battling stone-pelters.

Another picture shows a CRPF personnel in aggressive posture bent over with a baton in one hand, gun in another and a jackboot over a captured young protester’s shoulder. More tellingly, the action takes place under the cover of an armoured vehicle.

In yet another picture, a migrant worker mother and her adolescent son find a reason to dance in freezing Chillai Kalan outside their snow-covered shack. Amid the bleakness of the other images, this picture fills you with hope.

Showkat Nanda’s pictures, in comparison, exude more reflection than energy. And more than a fleeting, yet insightful, peep into the conflict, they offer you a deeper psychological exploration.

The shadow of a hooded slingshot protester drawn across a wall scrawled with template Azadi slogan, ‘Go India, Go Back’ is one such picture. It elevates an unremitting, livewire protest into an abstract art.

Or the picture of a small boy whose classmate has just been shot dead, throwing stones alone at a gargantuan armoured vehicle perched in the middle of a bridge. There is a telling difference in the relative position and the size of the boy and the vehicle – the boy standing lower down on the slope of the bridge and the armoured vehicle rising stealthily from behind the bunker – a symbolic representation of the oppression.

The book contains many more rare and unseen pictures dating back to 1986 which offer a searing glimpse of the conflict as it plays out on the ground. The Kashmir you see in Witness is unfiltered and unmediated by the words or a fleeting video and their implicit and explicit politics.

For once, you get to see and experience the situation in Kashmir like it is, not how it has to be seen and experienced so far.

Edited by Jhinuk Sen

First published: 22 March 2017, 16:29 IST