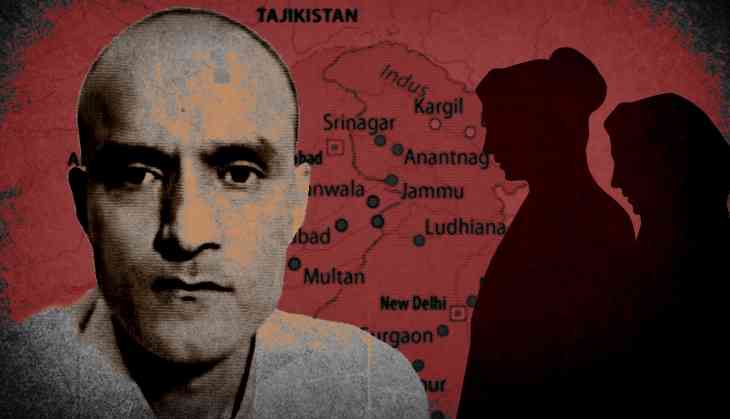

Caution please: India demands 'sovereign guarantee' from Pak govt for Kulbhushan Jadhav's wife & mother

India is proceeding cautiously in working out the modalities of Kulbhushan Jadhav’s wife's visit to Pakistan.

Pakistan had made an offer to arrange for Jadhav’s wife to meet him. It had stressed that its offer was on “purely humanitarian considerations”. As mentioned by this writer in an earlier analysis in these columns the offer is linked to the Jadhav case at the International Court of Justice.

India has demanded “sovereign guarantee” from the Pakistan government for Jadhav’s wife and her mother-in-law’s “safety and security”. It has also demanded that “during their visit, they should not be questioned or harassed”. The government has also asked that Pakistan allow “a diplomat to accompany” the ladies “at all times including the meeting” with Jadhav.

While the Pakistan offer is only for Jadhav’s wife the government has clarified that she would like her mother-in-law to accompany her.

It can be recalled that External Affairs Minister Sushma Swaraj had written to Sartaj Aziz, the then foreign policy advisor to the then Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif, asking Pakistan to arrange Jadhav’s mother’s visit so that she could meet her son. Jadhav has been sentenced to death by a Pakistani military court through a completely vitiated process. The charges against Jadhav are an obvious concoction. Pakistan had not cared to respond to Swaraj’s letter.

Prima facie none of the conditions that India wants Pakistan to fulfil are unreasonable. Certainly, the caution is entirely warranted. Clearly, also by asking that a diplomat be present at the wife and mother’s meeting with him India is not indirectly ensuring consular access. That stands on a different footing altogether.

The use of the term ‘sovereign guarantee’ and the requirement that the ladies should not be ‘questioned’ raise certain doubts which the government needs to clarify.

The term ‘sovereign guarantee’ is used in economic and commercial contexts for governments to underwrite loans and advances. Its use in a diplomatic context is unprecedented. Generally, when governments ask for measures for safety and security ‘firm assurances’ or ‘secure arrangements’ are sought.

Assuming the words ‘sovereign guarantee’ have been deliberately used, what are they meant to signify? Do they actually seek to really ensure that the contingency that Jadhav’s wife may be questioned does not arise?

This is not a far-fetched conjecture for it appears that the government may have good, but so far publicly undisclosed, reasons to believe that some institutions in Pakistan may be tempted to question Jadhav’s wife.

That may also be the reason why Sushma Swaraj had asked Pakistan to arrange for Jadhav’s mother’s visit and not that of his wife. Normally it would be expected that in such cases it is the wife who has the first right to meet someone in Jadhav’s situation.

Viewed from this angle the use of the term ‘sovereign guarantee’ obviously also seeks to ensure that no Pakistani court, civil or military, can order the government to make Jadhav’s wife available to be questioned in any matter related to the charges against her husband. If it transpires that a court does do so the Pakistani authorities will be expected after giving ‘sovereign guarantee’ to ensure that executive action is taken to render such an order ineffective.

The question, however, remains – why is the government going to such extraordinary lengths? For an answer, it would be useful to turn to the steps Pakistan has taken to seek to implicate the entire leadership of the Indian intelligence in the Jadhav concoction. This has been a very aggressive process.

While making Jadhav's arrest public on 29 March 2016, the Director-General of the Inter Services Public Relations (ISPR) Gen. Asim Bajwa had claimed that Jadhav had confessed that he was being controlled by the Indian NSA and the R&AW chief. Later case proceedings were launched against Jadhav in a military court.

While this process was underway and India was continuously asking Pakistan for consular access for Jadhav Pakistan sent a note on 23 January this year to India seeking assistance for collecting evidence in what it said was the criminal investigation relating to the Jadhav case.

While neither country has made that note public, Pakistan has given it to the judges of the ICJ. The Pakistani note identified 13 names as so-called accomplices of Jadhav. Till now the assumption, including by this writer, has been that these 13 are members of the Indian intelligence.

Given the nature of the Indian response to the Pakistani offer for Jadhav’s wife’s visit is it possible that there are some who are not connected with Intelligence matters find mention in that note? Is it that Pakistan has in some manner sought to embarrass some of Jadhav’s family members, including his wife?

For the time being, India has shown great restraint in not taking the step of revealing the details of Pakistan’s note of 23 January. Restraint is a wise policy if there is the hope that issue can be resolved by Pakistan abandoning the extremely provocative stance it has taken all through the Jadhav concoction.

Notwithstanding the offer for Jadhav’s wife’s visit, there is no public indication that Pakistan is wanting to change course in the matter.

Hence, the time may now have come to reveal the full extent of Pakistan’s perfidy in this matter unless there are good reasons for the government to feel that finally the matter, as all such cases, are resolved bilaterally through negotiations.