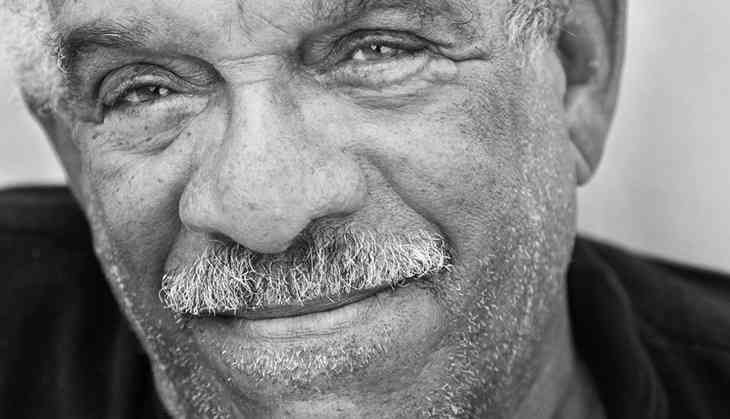

The world loses Derek Walcott, the man. But never the poet

Contemporary literature. That's how college curricula in India categorise Derek Walcott. Folded between pages of poetry from the likes of Maragaret Atwood and Pablo Neruda, Walcott makes a fine impression on the minds of the otherwise unimpressed.

The Caribbean poet from St Lucia died at 87 on Friday. But he leaves behind scrolls and scrolls of poetry, accessible words, identifiable realities, and, most of all, the constant loop of love and loss.

Walcott, best remembered for his epic poem Omeros, which won him the 1992 Nobel Prize for Literature, found inspiration in his roots. His written word traverses our shared colonial histories, the confusion in the cosmopolitan post-colonial, and the stronghold of a proud culture that refused to bow.

Walcott, best remembered for his epic poem Omeros, which won him the 1992 Nobel Prize for Literature, found inspiration in his roots. His written word traverses our shared colonial histories, the confusion in the cosmopolitan post-colonial, and the stronghold of a proud culture that refused to bow.

This, of course, is extremely relatable for most Indians, especially those who gain a window into the world through the very language of our colonial masters. In Omeros, which is a fascinating 64-chapter poem running into seven books, Walcott revisits the "Trojan War as a Caribbean fisherman's fight".

By appropriating what is arguably the most classic of the classics, Odyssey, Walcott creates a contemporary Omeros (or Homer) in a setting he understands. He subverts the colonial establishment of what is 'high culture' by recreating Homer's characters – Helen, Achilles, Hector – as multi-cultural, belonging to the colonised.

Walcott, in his own words

It would be a futile attempt to remember Walcott by any words other than his own. Deeply introspective, Walcott's writing is as much a window into his mind, troubles, aspirations, as it would be to the collective that is the colonised.

Talking about his love of poetry in a 2007 NPR interview, Walcott said his society and family encouraged his writing, especially his father, who wrote a bit of poetry himself.

"...the country that I was coming from, the island I was in, hadn't been written about, really. So I felt that I virtually had it all to myself, including the language that was spoken there, which was a French Creole, and a landscape that was not recorded, really. And a people. So it was a tremendous privilege to want to record all of that," he said.

Walcott allows himself to visit his reader, often directly communicating what he thinks, disrupting, albeit not jarringly, the flow of the text. In Omeros, for instance, he suddenly writes, "What I had read and rewritten till literature / was guilty as History."

"When would it stop, / the echo in the throat, insisting, `Omeros'; / when would I enter the light beyond metaphor?" Walcott often loses himself in Homer, blending the two, as both their truths merge.

In other poems, such as The Schooner Flight, he quite directly references the struggle of multiple identitities.

I’m just a red nigger who love the sea,

I had a sound colonial education,

I have Dutch, nigger, and English in me,

and either I’m nobody, or I’m a nation.

In A Far Cry From Africa, Walcott expresses anguish at this dichotomy.

I who am poisoned with the blood of both,

Where shall I turn, divided to the vein?

I who have cursed

The drunken officer of British rule, how choose

Between this Africa and the English tongue I love?

Betray them both, or give back what they give?

How can I face such slaughter and be cool?

How can I turn from Africa and live?

In Love After Love, Walcott forays into how these identities can also change, form, break, reform with time.

The time will come

when, with elation,

you will greet yourself arriving

at your own door, in your own mirror,

and each will smile at the other’s welcome,

and say, sit here. Eat.

You will love again the stranger who was your self.

Give wine. Give bread. Give back your heart

to itself, to the stranger who has loved you

all your life, whom you ignored

for another, who knows you by heart.

Take down the love letters from the bookshelf,

the photographs, the desperate notes,

peel your own image from the mirror.

Sit. Feast on your life.

With Endings, he establishes how loss, be it of your own self, a loved one, or a cherished thing, comes with decay. "Things do not explode, / they fail, they fade," he writes.

...as sunlight fades from the flesh,

as the foam drains quick in the sand,

even love’s lightning flash

has no thunderous end,

it dies with the sound

of flowers fading like the flesh

from sweating pumice stone,

everything shapes this

till we are left

with the silence that surrounds Beethoven’s head.

In Midsummer, Tobago, he further explores time, and the loss that comes with time.

Days I have held,

days I have lost,

Days that outgrow, like daughters,

my harbouring arms.

And ultimately, in To Norline, a poem written for his wife as he fears losing her, he explores the ephemeral nature of life and love as himself, as well as the possibility of being replaced by another.

This beach will remain empty

for more slate-coloured dawns

of lines the surf continually

erases with its sponge,

and someone else will come

from the still-sleeping house,

a coffee mug warming his palm

as my body once cupped yours,

to memorize this passage

of a salt-sipping tern,

like when some line on a page

is loved, and it's hard to turn.

Walcott's poetry is lucid. With utmost clarity he dissects his own life and world to present his readers with a picture not so far removed from their lives.

His writing remains in the present, and will continue to in the foreseeable future. That may very well be why we never have to speak of him in the past tense.

First published: 18 March 2017, 18:49 IST