Pen & sword in Mughal court: The lives of Abdur Rahim Khan-i-Khanan & Bairam Khan

“Rahiman chup ho baithiye, dekhi dinan ko pher, Jab nike din aayihe, banat na lagiye der.” (Sit out the bad days quietly, because when the good days arrive, it doesn’t take long for fortunes to turn)

This doha, commonly ascribed to Abdur Rahim Khan-i-Khanan, underlines the transient nature of fate and seems a fitting way to launch an inquiry chronicling the ebb and flow in the fortunes of two Mughal nobles most of us are familiar with, Mirza Abdur Rahim and his father, Bairam Khan.

The institution of Mughal nobility, with its myriad racial and ethnic alignments, is one of the most fascinating aspects of medieval Indian historiography. The nature and role of the various dispensations of the Mughal ruling elite, the complex working of ethnic/clan ties amongst them, the jostling for power with the imperial centre and the ephemeral nature of their alliances and cliques has received much scholarly attention in the past few decades.

Former diplomat TCA Raghavan’s debut undertaking is a noteworthy inclusion to the corpus of work on such themes. In Attendant Lords: Bairam Khan and Abdur Rahim, Courtiers and Poets in Mughal World, he painstakingly reconstructs the life and times of two of these two significant nobles of 16th and early 17th Century Mughal India.

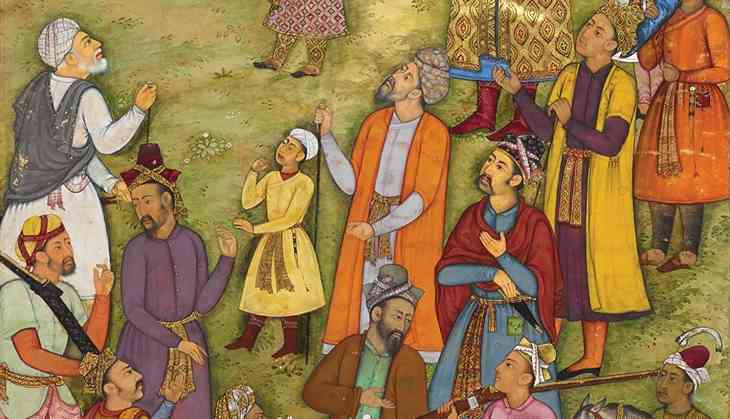

Both these men were not just prominent courtiers and formidable military commanders that is men of the sword (Ahl-i-Saif) but possessed considerable literary skills and are rightly termed by the author as being noted men of letters (Ahl-i-Qalam). Rightfully so then, the author approaches this account as not being merely a political biography of his subjects but seeks to locate it at the cross-section of larger historical developments and 20th century debates over language, literary traditions, religion and nationalism.

The political, military and cultural achievements of the two nobles are narrated by Raghavan with textbook precision, but what makes his work topical is the attempt to document the afterlife and continued relevance of these two men, especially Abdur Rahim Khan-i-Khanan: the celebrated Rahim best known for his eponymous Hindi dohas.

_66039.jpg)

The book begins with Bairam Khan (1497-1561), a ‘Persianised’ Turk from the powerful Qara Qoyunlu tribal federation, who had entered Babur’s court in A.D.1512-13 and rose to prominence by playing a crucial role during Humayun’s exile in Safavid Persia and the subsequent reconsolidation of the Mughal Empire in Hindustan.

After Humayun’s sudden death, he had the enviable position of being a tutor (Ataliq) and regent (Vakil) to the young prince, Akbar. With a gripping retelling of how Bairam lost favour with the new Emperor and his swift fall from grace, Raghavan moves on to the actual focus of his work. The focal point is Bairam’s son, Abdur Rahim (1556- 1626); courtier, commander, poet and patron par excellence, who lies buried not far from Humayun’s Tomb, in a tomb he had built for his wife, Mah Banu, a Mewati princess.

Recreating 'Rahim'

Many find it difficult to reconcile Abdur Rahim Khan-i-Khanan, Akbar’s pragmatic military commander and seasoned Mughal statesman, with the prolific writer of sensuous ‘Nayika Bhed’ verses, ‘bhakti’-inspired devotional songs and succinctly written couplets (dohe) that most of us were introduced to in our school life.

Raghavan undertakes this very challenge, bringing together the two disparate parts of Abdur Rahim’s life to present us with a glimpse of a man who lived a rich, multi-faceted, often contradictory life, reflecting the vagaries of the time and milieu he lived in.

His meteoric ascension in the imperial hierarchy had placed him at the centre of some of the most important developments of Akbar (and Jahangir’s) reign – the expansion of the empire and the intellectual ferment and religious eclecticism which characterised the period. Concomitant to his military successes during the Gujarat and Deccan campaigns, which had cemented his status as an indispensable component of the Mughal machinery, he had also come to be highly regarded for his literary acumen and the patronage to Persian, Urdu, Sanskrit and Hindi poets and artists.

His celebrated library with its extensive collection of rare illustrated manuscripts including Amir Khusrau’s Khamsa, Firdausi’s Shahnama and the Persian translations of the Ramayana, was visited by hundreds of scholars every day. Raghavan tries to trace the evolution of both the sides of Rahim’s career, a task somewhat hampered by the lack of definite chronological markers in Rahim’s literary work and the contentious authorship of many oral/written compositions now assigned to him.

It is the afterlife of Rahim, the poet, that most interests the author. He looks at how different legacies of Rahim were fashioned over a period of time, resulting in his being regarded as one of the foremost ‘Hindi’ poets and a national icon today. To understand why this was so, despite contemporary writers and anthologies on Hindi literature composed before 19th century showing scant attention to Rahim’s literary contributions, Raghavan delves into the larger politics of the period.

Late 19th-early 20th century was associated with the excision of Urdu and Hindi into separate linguistic and literary traditions, the burgeoning of the Devanagiri movement and the rising demands for standardising and demarcating Hindi as the language of Hindus and India. Rahim, with his Hindi verses and the liberal usage of ‘Hindu/Bhakti’ idioms and themes was seen as the ideal ‘Muslim’ noble who had great affinity for Vaishnavism and was soon co-opted to serve larger national goals.

Not surprisingly, he received much attention in the Hindi literary world and entered school curricula and popular imagination as a national icon of ‘Indianess’ and statesman of Hindu-Muslim unity in a nation which was in the early throes of nation-building. The near silence of Urdu literary tradition on Rahim’s accomplishments as a Hindi poet, while they celebrated his Persian writings, points to a similar process at work.

The book, well-researched and eminently readable, suffers from a few misprints and errors. Khanzadeh Begum, Babur’s widowed sister is mentioned as his widow and a few dates are misprinted. The reader is also left wanting for a glimpse of Rahim’s pithy original compositions, as almost all of the verses and couplets are given in English. But Raghavan effectively manages to sift through the folds of popular imagination and historical realities in order to shed light on the processes which have resulted in the appropriation of historical figures and events so that they neatly fit the contours of present day language and identity politics. The aphorism that history is as much about forgetting as it is about remembering has never seemed truer.

The writer teaches history at St. Stephen's College, University of Delhi

First published: 17 June 2017, 18:38 IST