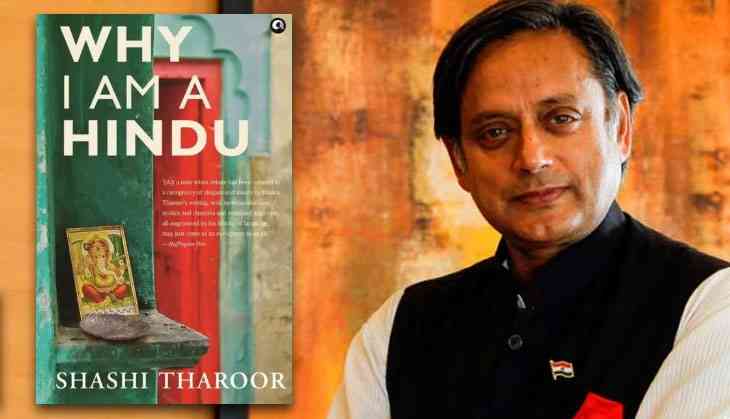

Why I am a Hindu book review: Shashi Tharoor takes on political Hindutva with his personal Hinduism

Hinduism has been debated over and defined innumerable times by an array of theologians, sages, kings and philosophers. Going by the records of interpretations of Hinduism, it would be difficult to point out one particular way or ritual that could be defined as peculiarly Hindu. From the Vedas, to the Upanishads and the Puranas, one finds a number of different, often contradictory versions on the Hindu philosophy and rituals attached to it.

In this context, the title of Shashi Tharoor’s new volume ‘Why I am a Hindu', makes it clear that the politician-author is staying away from prescribing his Hinduism to others. He is putting out his understanding of the religion that he was born in and in the process raises questions for his readers to ponder before blindly subscribing to any interpretation of this millennia-old religion.

Why a book on Hinduism by a Congress politician?

The idea of political Hinduism was first introduced by Mahatma Gandhi during India’s freedom movement against the British. It is believed that without Gandhi’s call for a Ram Rajya – essentially a Hindu theocratic state – it would not have been possible for Indian National Congress to become a party of the masses.

However, soon after Gandhi fired the imaginations of the masses with his idea of a Ram Rajya, a section of Hindu hardliners (including Rashtriya Swayamsewak Sangh or RSS) emerged. Over the years, it redefined the meaning of Ram Rajya – focusing on aggressive analogies from the religious traditions of Hinduism in an attempt to give a monotheistic face to a religion that had evolved in a polytheistic manner.

This changed Hinduism is fast becoming popular and has given a clear majority to a non-Congress party only the second time since Independence.

Given the role that religion has played in Indian politics, since the days of freedom struggle, Tharoor’s theological polemic is an attempt at reclaiming the fast fading idea of Hinduism that helped Gandhi to move the masses- from the RSS version of it under the nomenclature of Hindutva (a term coined by BJP’s icon, VD Savarkar).

Tharoor is a prolific writer with close to two dozen titles to his name that deal with varied subjects ranging from politics, history, sociology, culture and religion. This kind of scholarship, takes Tharoor closer to the legacy of none other than Jawaharlal Nehru, who in his book, ‘Discovery Of India’ also made an attempt to explain Hindu traditions and its ever evolving nature to accommodate newer streams of philosophy that emerged with the passage of time.

Nehru talked about the reasons behind the fall of Indian Civilization that surrendered to the British. Tharoor, in his thesis on Hinduism, is drawing attention to the immediate danger that looms over this age-old civilisation due to the emergence of an exclusivist interpretation of an inclusive way of life.

Tharoor, quotes with ease chronologically from Vedas, Upanishads, Puranas, epics to put forth an idea that while each of the sacred texts that are part of Hinduism are important none of them can claim to be superior to the other:

“ Hinduism has not one sacred book, but several, both complementary and contradictory to each other. The Hindu scriptures are commonly divided into Srutis, Smritis, Itihasas, Puranas, Agamas and Darshanas.”

Since Tharoor is countering RSS/BJP-supported Hindutva, which has entered the kitchens of people enforcing upon them the eating habits of North Indian Brahmins, he quotes the tradition of ‘animal sacrifices’, in the Rig Veda, “including those of cattle.”

Giving vivid description of the six Indian philosophical schools of thought, Tharoor, argues that Hinduism has the tradition of even accepting atheism – unlike Abrahmic religions – therefore any attempt to limit it to a particular ritual or any one religious book would be against the essence of the tradition of the Indian civilisation that has travelled a long way from the days of Indus Valley Civilisation.

Whose Hinduism should Indians espouse? Vivekananda’s or Golwalkar’s?

While the BJP, as a part of its project to consolidate the Hindu philosophy has tried to selectively appropriate certain Hindu philosophers, Tharoor, cleverly, for his readers brings alive many more souls who have contributed to the tradition of this religion. Tharoor does not stop there, he pitches the philosophy of Vivekananda against that of Golwalkar.

Quoting Swami Vivekananda’s speech to the Chicago convention in which he defended the idea of freedom to choose one’s way of worshiping God, Tharoor builds a narrative against the later Hindutva ideologues who the BJP takes inspiration from.

“Unity in variety is the plan of nature, and the Hindu has recognized it. Every other religion lays down certain fixed dogmas and tries to compel the society to adopt them. It places before society only one coat which must fit Jack and John and Henry, all alike. If it does not fit John or Henry, he must go without Coat to cover his body. The Hindus have discovered that the absolute can only be realized or thought of or stated through the relative and the images, crosses and crescents are simply so many symbols – so many pegs to hang spiritual ideas on. It is not that this help is necessary for everyone, but those that do not need it have no right to say that it is wrong. Nor is it compulsory in Hinduism.”

Compare the above mentioned idea of Vivekananda with the following one put forth by M.S Golwalkar- the second Sarsanghchalak of the RSS in his treatise ‘ We, or our Nationahood defined’: “To keep up the purity of the race and its culture, Germany shocked the world by her purging the country of the Semitic Races – the Jews. Race pride at its highest has been manifested here. Germany has also shown how well nigh impossible it is for Races and cultures, having differences going to the root, to be assimilated into one united Whole, a good lesson for us In Hindustan to learn and profit by.”

Tharoor, by drawing comparison between two different streams of thoughts on the idea of India, nature and its culture, leaves it to his readers to take a call on what type of Hinduism would they want to espouse – Vivekanada’s or Golwalkar’s ?

Tharoor has not kept his book limited to dealing with only the ancient values of Hinduism. The second part of his book defines the limits and possibilities of a modern India. He talks about hunger, poverty, Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code and secularism. It is an attempt by Tharoor to prescribe the assimilation of newer democratic values in this age old religion.

By doing so, he widens the scope of his book from being concerned with only theological pursuits, to something that concerns sociology and constitutional debates as well.

The battle between Hindusim and Hindutva is unlikely to be resolved anytime soon, more so because the propounders of the latter after a struggle of close to 100 years have built their stronghold among a sizeable chunk of the country’s population.

But such books are not written for immediate results. It is aimed at taking on the idea of exclusivist identity of Hinduism- something that takes selectively from the past to serve the political purposes of the present.

Why I am a Hindu is an important addition in the tradition of intra-religion theological debate. How these ideas percolate down among followers of Hinduism will decide the future course of India's politics.